In this blog post, I am going to teach you how to train a Bayesian deep learning classifier using Keras and tensorflow. Before diving into the specific training example, I will cover a few important high level concepts:

- What is Bayesian deep learning?

- What is uncertainty?

- Why is uncertainty important?

I will then cover two techniques for including uncertainty in a deep learning model and will go over a specific example using Keras to train fully connected layers over a frozen ResNet50 encoder on the cifar10 dataset. With this example, I will also discuss methods of exploring the uncertainty predictions of a Bayesian deep learning classifier and provide suggestions for improving the model in the future.

This post is based on material from two blog posts (here and here) and a white paper on Bayesian deep learning from the University of Cambridge machine learning group. If you want to learn more about Bayesian deep learning after reading this post, I encourage you to check out all three of these resources. Thank you to the University of Cambridge machine learning group for your amazing blog posts and papers.

Bayesian statistics is a theory in the field of statistics in which the evidence about the true state of the world is expressed in terms of degrees of belief. The combination of Bayesian statistics and deep learning in practice means including uncertainty in your deep learning model predictions. The idea of including uncertainty in neural networks was proposed as early as 1991. Put simply, Bayesian deep learning adds a prior distribution over each weight and bias parameter found in a typical neural network model. In the past, Bayesian deep learning models were not used very often because they require more parameters to optimize, which can make the models difficult to work with. However, more recently, Bayesian deep learning has become more popular and new techniques are being developed to include uncertainty in a model while using the same number of parameters as a traditional model.

Visualizing a Bayesian deep learning model.

What is uncertainty?

Uncertainty is the state of having limited knowledge where it is impossible to exactly describe the existing state, a future outcome, or more than one possible outcome. As it pertains to deep learning and classification, uncertainty also includes ambiguity; uncertainty about human definitions and concepts, not an objective fact of nature.

An example of ambiguity. What should the model predict?

There are several different types of uncertainty and I will only cover two important types in this post.

Aleatoric uncertainty measures what you can't understand from the data. It can be explained away with the ability to observe all explanatory variables with increased precision. Think of aleatoric uncertainty as sensing uncertainty. There are actually two types of aleatoric uncertainty, heteroscedastic and homoscedastic, but I am only covering heteroscedastic uncertainty in this post. Homoscedastic is covered more in depth in this blog post.

Concrete examples of aleatoric uncertainty in stereo imagery are occlusions (parts of the scene a camera can't see), lack of visual features (i.e a blank wall), or over/under exposed areas (glare & shading).

Occlusions example

Lack of visual features example

Under/over exposed example

Epistemic uncertainty measures what your model doesn't know due to lack of training data. It can be explained away with infinite training data. Think of epistemic uncertainty as model uncertainty.

An easy way to observe epistemic uncertainty in action is to train one model on 25% of your dataset and to train a second model on the entire dataset. The model trained on only 25% of the dataset will have higher average epistemic uncertainty than the model trained on the entire dataset because it has seen fewer examples.

A fun example of epistemic uncertainty was uncovered in the now famous Not Hotdog app. From my own experiences with the app, the model performs very well. But upon closer inspection, it seems like the network was never trained on "not hotdog" images that included ketchup on the item in the image. So if the model is shown a picture of your leg with ketchup on it, the model is fooled into thinking it is a hotdog. A Bayesian deep learning model would predict high epistemic uncertainty in these situations.

If there's ketchup, it's a hotdog @FunnyAsianDude #nothotdog #NotHotdogchallenge pic.twitter.com/ZOQPqChADU

— David (@david__kha) May 18, 2017

In machine learning, we are trying to create approximate representations of the real world. Popular deep learning models created today produce a point estimate but not an uncertainty value. Understanding if your model is under-confident or falsely over-confident can help you reason about your model and your dataset. The two types of uncertainty explained above are import for different reasons.

Note: In a classification problem, the softmax output gives you a probability value for each class, but this is not the same as uncertainty. The softmax probability is the probability that an input is a given class relative to the other classes. Because the probability is relative to the other classes, it does not help explain the model’s overall confidence.

Aleatoric uncertainty is important in cases where parts of the observation space have higher noise levels than others. For example, aleatoric uncertainty played a role in the first fatality involving a self driving car. Tesla has said that during this incident, the car's autopilot failed to recognize the white truck against a bright sky. An image segmentation classifier that is able to predict aleatoric uncertainty would recognize that this particular area of the image was difficult to interpret and predicted a high uncertainty. In the case of the Tesla incident, although the car's radar could "see" the truck, the radar data was inconsistent with the image classifier data and the car's path planner ultimately ignored the radar data (radar data is known to be noisy). If the image classifier had included a high uncertainty with its prediction, the path planner would have known to ignore the image classifier prediction and use the radar data instead (this is oversimplified but is effectively what would happen. See Kalman filters below).

Even for a human, driving when roads have lots of glare is difficult

Epistemic uncertainty is important because it identifies situations the model was never trained to understand because the situations were not in the training data. Machine learning engineers hope our models generalize well to situations that are different from the training data; however, in safety critical applications of deep learning hope is not enough. High epistemic uncertainty is a red flag that a model is much more likely to make inaccurate predictions and when this occurs in safety critical applications, the model should not be trusted.

Epistemic uncertainty is also helpful for exploring your dataset. For example, epistemic uncertainty would have been helpful with this particular neural network mishap from the 1980s. In this case, researchers trained a neural network to recognize tanks hidden in trees versus trees without tanks. After training, the network performed incredibly well on the training set and the test set. The only problem was that all of the images of the tanks were taken on cloudy days and all of the images without tanks were taken on a sunny day. The classifier had actually learned to identify sunny versus cloudy days. Whoops.

Tank & cloudy vs no tank & sunny

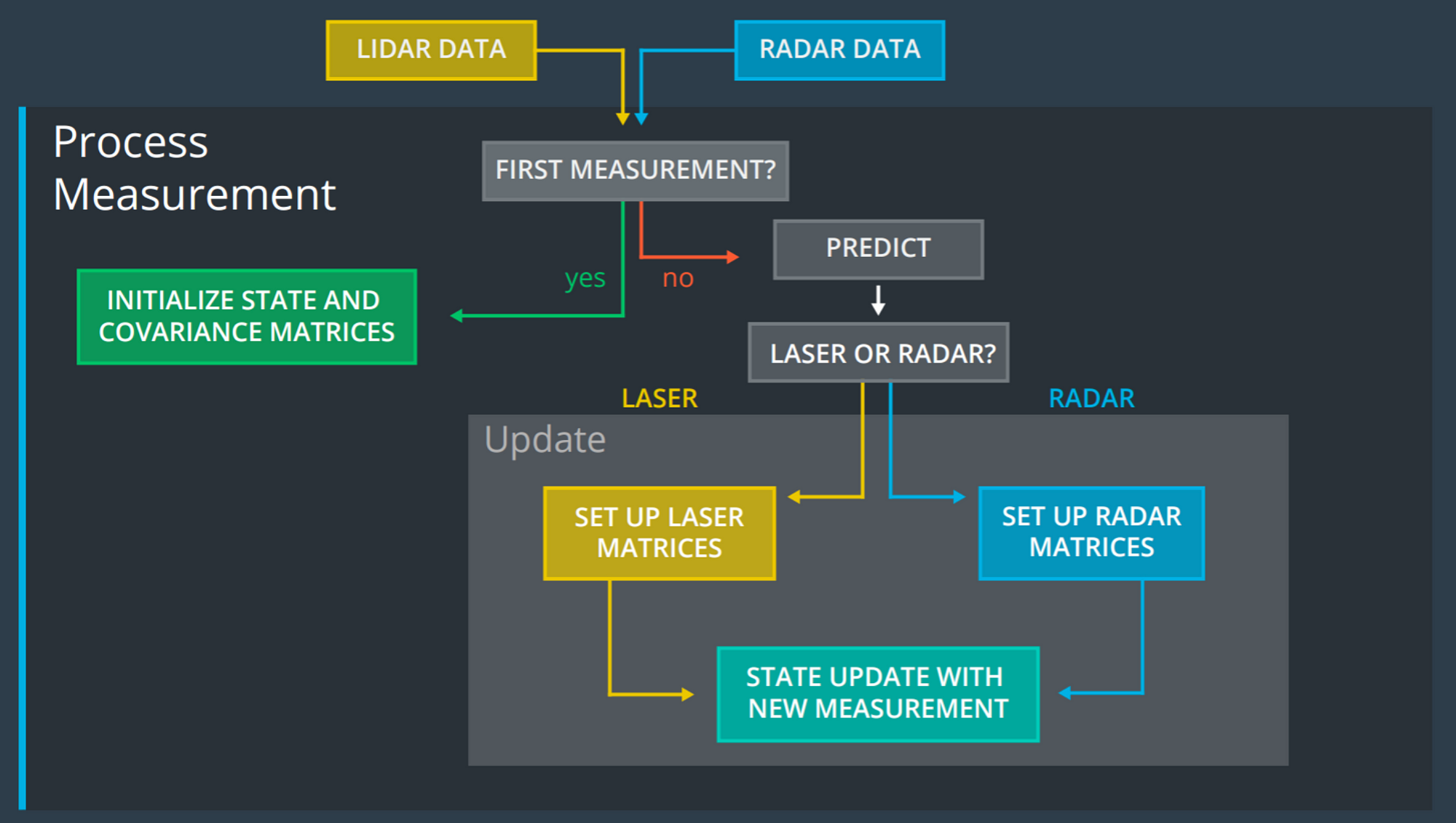

Uncertainty predictions in deep learning models are also important in robotics. I am currently enrolled in the Udacity self driving car nanodegree and have been learning about techniques cars/robots use to recognize and track objects around then. Self driving cars use a powerful technique called Kalman filters to track objects. Kalman filters combine a series of measurement data containing statistical noise and produce estimates that tend to be more accurate than any single measurement. Traditional deep learning models are not able to contribute to Kalman filters because they only predict an outcome and do not include an uncertainty term. In theory, Bayesian deep learning models could contribute to Kalman filter tracking.

Radar and lidar data merged into the Kalman filter. Image data could be incorporated as well.

Aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty are different and, as such, they are calculated differently.

Aleatoric uncertainty is a function of the input data. Therefore, a deep learning model can learn to predict aleatoric uncertainty by using a modified loss function. For a classification task, instead of only predicting the softmax values, the Bayesian deep learning model will have two outputs, the softmax values and the input variance. Teaching the model to predict aleatoric variance is an example of unsupervised learning because the model doesn't have variance labels to learn from. Below is the standard categorical cross entropy loss function and a function to calculate the Bayesian categorical cross entropy loss.

import numpy as np

from keras import backend as K

from tensorflow.contrib import distributions

# standard categorical cross entropy

# N data points, C classes

# true - true values. Shape: (N, C)

# pred - predicted values. Shape: (N, C)

# returns - loss (N)

def categorical_cross_entropy(true, pred):

return np.sum(true * np.log(pred), axis=1)

# Bayesian categorical cross entropy.

# N data points, C classes, T monte carlo simulations

# true - true values. Shape: (N, C)

# pred_var - predicted logit values and variance. Shape: (N, C + 1)

# returns - loss (N,)

def bayesian_categorical_crossentropy(T, num_classes):

def bayesian_categorical_crossentropy_internal(true, pred_var):

# shape: (N,)

std = K.sqrt(pred_var[:, num_classes:])

# shape: (N,)

variance = pred_var[:, num_classes]

variance_depressor = K.exp(variance) - K.ones_like(variance)

# shape: (N, C)

pred = pred_var[:, 0:num_classes]

# shape: (N,)

undistorted_loss = K.categorical_crossentropy(pred, true, from_logits=True)

# shape: (T,)

iterable = K.variable(np.ones(T))

dist = distributions.Normal(loc=K.zeros_like(std), scale=std)

monte_carlo_results = K.map_fn(gaussian_categorical_crossentropy(true, pred, dist, undistorted_loss, num_classes), iterable, name='monte_carlo_results')

variance_loss = K.mean(monte_carlo_results, axis=0) * undistorted_loss

return variance_loss + undistorted_loss + variance_depressor

return bayesian_categorical_crossentropy_internal

# for a single monte carlo simulation,

# calculate categorical_crossentropy of

# predicted logit values plus gaussian

# noise vs true values.

# true - true values. Shape: (N, C)

# pred - predicted logit values. Shape: (N, C)

# dist - normal distribution to sample from. Shape: (N, C)

# undistorted_loss - the crossentropy loss without variance distortion. Shape: (N,)

# num_classes - the number of classes. C

# returns - total differences for all classes (N,)

def gaussian_categorical_crossentropy(true, pred, dist, undistorted_loss, num_classes):

def map_fn(i):

std_samples = K.transpose(dist.sample(num_classes))

distorted_loss = K.categorical_crossentropy(pred + std_samples, true, from_logits=True)

diff = undistorted_loss - distorted_loss

return -K.elu(diff)

return map_fnThe loss function I created is based on the loss function in this paper. In the paper, the loss function creates a normal distribution with a mean of zero and the predicted variance. It distorts the predicted logit values by sampling from the distribution and computes the softmax categorical cross entropy using the distorted predictions. The loss function runs T Monte Carlo samples and then takes the average of the T samples as the loss.

Figure 1: Softmax categorical cross entropy vs. logit difference for binary classification

In Figure 1, the y axis is the softmax categorical cross entropy. The x axis is the difference between the 'right' logit value and the 'wrong' logit value. 'right' means the correct class for this prediction. 'wrong' means the incorrect class for this prediction. I will use the term 'logit difference' to mean the x axis of Figure 1. When the 'logit difference' is positive in Figure 1, the softmax prediction will be correct. When 'logit difference' is negative, the prediction will be incorrect. I will continue to use the terms 'logit difference', 'right' logit, and 'wrong' logit this way as I explain the aleatoric loss function.

Figure 1 is helpful for understanding the results of the normal distribution distortion. When the logit values (in a binary classification) are distorted using a normal distribution, the distortion is effectively creating a normal distribution with a mean of the original predicted 'logit difference' and the predicted variance as the distribution variance. Applying softmax cross entropy to the distorted logit values is the same as sampling along the line in Figure 1 for a 'logit difference' value.

Taking the categorical cross entropy of the distorted logits should ideally result in a few interesting properties.

- When the predicted logit value is much larger than any other logit value (the right half of Figure 1), increasing the variance should only increase the loss. This is true because the derivative is negative on the right half of the graph. i.e. increasing the 'logit difference' results in only a slightly smaller decrease in softmax categorical cross entropy compared to an equal decrease in 'logit difference'. The minimum loss should be close to 0 in this case.

- When the 'wrong' logit is much larger than the 'right' logit (the left half of graph) and the variance is ~0, the loss should be ~

wrong_logit-right_logit. You can see this is on the right half of Figure 1. When the 'logit difference' is -4, the softmax cross entropy is 4. The slope on this part of the graph is ~ -1 so this should be true as the 'logit difference' continues to decrease. - To enable the model to learn aleatoric uncertainty, when the 'wrong' logit value is greater than the 'right' logit value (the left half of graph), the loss function should be minimized for a variance value greater than 0. For an image that has high aleatoric uncertainty (i.e. it is difficult for the model to make an accurate prediction on this image), this feature encourages the model to find a local loss minimum during training by increasing its predicted variance.

I was able to use the loss function suggested in the paper to decrease the loss when the 'wrong' logit value is greater than the 'right' logit value by increasing the variance, but the decrease in loss due to increasing the variance was extremely small (<0.1). During training, my model had a hard time picking up on this slight local minimum and the aleatoric variance predictions from my model did not make sense. I believe this happens because the slope of Figure 1 on the left half of the graph is ~ -1. Sampling a normal distribution along a line with a slope of -1 will result in another normal distribution and the mean will be about the same as it was before but what we want is for the mean of the T samples to decrease as the variance increases.

To make the model easier to train, I wanted to create a more significant loss change as the variance increases. Just like in the paper, my loss function above distorts the logits for T Monte Carlo samples using a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and the predicted variance and then computes the categorical cross entropy for each sample. To get a more significant loss change as the variance increases, the loss function needed to weight the Monte Carlo samples where the loss decreased more than the samples where the loss increased. My solution is to use the elu activation function, which is a non-linear function centered around 0.

ELU activation function

I applied the elu function to the change in categorical cross entropy, i.e. the original undistorted loss compared to the distorted loss, undistorted_loss - distorted_loss. The elu shifts the mean of the normal distribution away from zero for the left half of Figure 1. The elu is also ~linear for very small values near 0 so the mean for the right half of Figure 1 stays the same.

Figure 2: Average change in loss & distorted average change in loss.

In Figure 2 right < wrong corresponds to a point on the left half of Figure 1 and wrong < right corresponds to a point on the right half of Figure 2. You can see that the distribution of outcomes from the 'wrong' logit case, looks similar to the normal distribution and the 'right' case is mostly small values near zero. After applying -elu to the change in loss, the mean of the right < wrong becomes much larger. In this example, it changes from -0.16 to 0.25. The mean of the wrong < right stays about the same. I call the mean of the lower graphs in Figure 2 the 'distorted average change in loss'. The 'distorted average change in loss' should should stay near 0 as the variance increases on the right half of Figure 1 and should always increase when the variance increases on the right half of Figure 1.

I then scaled the 'distorted average change in loss' by the original undistorted categorical cross entropy. This is done because the distorted average change in loss for the wrong logit case is about the same for all logit differences greater than three (because the derivative of the line is 0). To ensure the loss is greater than zero, I add the undistorted categorical cross entropy. The ‘distorted average change in loss’ always decreases as the variance increases but the loss function should be minimized for a variance value less than infinity. To ensure the variance that minimizes the loss is less than infinity, I add the exponential of the variance term. As Figure 3 shows, the exponential of the variance is the dominant characteristic after the variance passes 2.

Figure 3: Aleatoric variance vs loss for different 'wrong' logit values

Figure 4: Minimum aleatoric variance and minimum loss for different 'wrong' logit values

These are the results of calculating the above loss function for binary classification example where the 'right' logit value is held constant at 1.0 and the 'wrong' logit value changes for each line. When the 'wrong' logit value is less than 1.0 (and thus less than the 'right' logit value), the minimum variance is 0.0. As the wrong 'logit' value increases, the variance that minimizes the loss increases.

Note: When generating this graph, I ran 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations to create smooth lines. When training the model, I only ran 100 Monte Carlo simulations as this should be sufficient to get a reasonable mean.

Brain overload? Grab a time appropriate beverage before continuing.

One way of modeling epistemic uncertainty is using Monte Carlo dropout sampling (a type of variational inference) at test time. For a full explanation of why dropout can model uncertainty check out this blog and this white paper white paper. In practice, Monte Carlo dropout sampling means including dropout in your model and running your model multiple times with dropout turned on at test time to create a distribution of outcomes. You can then calculate the predictive entropy (the average amount of information contained in the predictive distribution).

To understand using dropout to calculate epistemic uncertainty, think about splitting the cat-dog image above in half vertically.

If you saw the left half, you would predict dog. If you saw the right half you would predict cat. A perfect 50-50 split. This image would high epistemic uncertainty because the image exhibits features that you associate with both a cat class and a dog class.

Below are two ways of calculating epistemic uncertainty. They do the exact same thing, but the first is simpler and only uses numpy. The second uses additional Keras layers (and gets GPU acceleration) to make the predictions.

# model - the trained classifier(C classes)

# where the last layer applies softmax

# X_data - a list of input data(size N)

# T - the number of monte carlo simulations to run

def montecarlo_prediction(model, X_data, T):

# shape: (T, N, C)

predictions = np.array([model.predict(X_data) for _ in range(T)])

# shape: (N, C)

prediction_probabilities = np.mean(predictions, axis=0)

# shape: (N)

prediction_variances = np.apply_along_axis(predictive_entropy, axis=1, arr=prediction_probabilities)

return (prediction_probabilities, prediction_variances)

# prob - prediction probability for each class(C). Shape: (N, C)

# returns - Shape: (N)

def predictive_entropy(prob):

return -1 * np.sum(np.log(prob) * prob, axis=1)from keras.models import Model

from keras.layers import Input, RepeatVector

from keras.engine.topology import Layer

from keras.layers.wrappers import TimeDistributed

# Take a mean of the results of a TimeDistributed layer.

# Applying TimeDistributedMean()(TimeDistributed(T)(x)) to an

# input of shape (None, ...) returns output of same size.

class TimeDistributedMean(Layer):

def build(self, input_shape):

super(TimeDistributedMean, self).build(input_shape)

# input shape (None, T, ...)

# output shape (None, ...)

def compute_output_shape(self, input_shape):

return (input_shape[0],) + input_shape[2:]

def call(self, x):

return K.mean(x, axis=1)

# Apply the predictive entropy function for input with C classes.

# Input of shape (None, C, ...) returns output with shape (None, ...)

# Input should be predictive means for the C classes.

# In the case of a single classification, output will be (None,).

class PredictiveEntropy(Layer):

def build(self, input_shape):

super(PredictiveEntropy, self).build(input_shape)

# input shape (None, C, ...)

# output shape (None, ...)

def compute_output_shape(self, input_shape):

return (input_shape[0],)

# x - prediction probability for each class(C)

def call(self, x):

return -1 * K.sum(K.log(x) * x, axis=1)

def create_epistemic_uncertainty_model(checkpoint, epistemic_monte_carlo_simulations):

model = load_saved_model(checkpoint)

inpt = Input(shape=(model.input_shape[1:]))

x = RepeatVector(epistemic_monte_carlo_simulations)(inpt)

# Keras TimeDistributed can only handle a single output from a model :(

# and we technically only need the softmax outputs.

hacked_model = Model(inputs=model.inputs, outputs=model.outputs[1])

x = TimeDistributed(hacked_model, name='epistemic_monte_carlo')(x)

# predictive probabilities for each class

softmax_mean = TimeDistributedMean(name='epistemic_softmax_mean')(x)

variance = PredictiveEntropy(name='epistemic_variance')(softmax_mean)

epistemic_model = Model(inputs=inpt, outputs=[variance, softmax_mean])

return epistemic_model

# 1. Load the model

# 2. compile the model

# 3. Set learning phase to train

# 4. predict

def predict():

model = create_epistemic_uncertainty_model('model.ckpt', 100)

model.compile(...)

# set learning phase to 1 so that Dropout is on. In keras master you can set this

# on the TimeDistributed layer

K.set_learning_phase(1)

epistemic_predictions = model.predict(data)Note: Epistemic uncertainty is not used to train the model. It is only calculated at test time (but during a training phase) when evaluating test/real world examples. This is different than aleatoric uncertainty, which is predicted as part of the training process. Also, in my experience, it is easier to produce reasonable epistemic uncertainty predictions than aleatoric uncertainty predictions.

Besides the code above, training a Bayesian deep learning classifier to predict uncertainty doesn't require much additional code beyond what is typically used to train a classifier.

def resnet50(input_shape):

input_tensor = Input(shape=input_shape)

base_model = ResNet50(include_top=False, input_tensor=input_tensor)

# freeze encoder layers to prevent over fitting

for layer in base_model.layers:

layer.trainable = False

output_tensor = Flatten()(base_model.output)

return Model(inputs=input_tensor, outputs=output_tensor)For this experiment, I used the frozen convolutional layers from Resnet50 with the weights for ImageNet to encode the images. I initially attempted to train the model without freezing the convolutional layers but found the model quickly became over fit.

def create_bayesian_model(encoder, input_shape, output_classes):

encoder_model = resnet50(input_shape)

input_tensor = Input(shape=encoder_model.output_shape[1:])

x = BatchNormalization(name='post_encoder')(input_tensor)

x = Dropout(0.5)(x)

x = Dense(500, activation='relu')(x)

x = BatchNormalization()(x)

x = Dropout(0.5)(x)

x = Dense(100, activation='relu')(x)

x = BatchNormalization()(x)

x = Dropout(0.5)(x)

logits = Dense(output_classes)(x)

variance_pre = Dense(1)(x)

variance = Activation('softplus', name='variance')(variance_pre)

logits_variance = concatenate([logits, variance], name='logits_variance')

softmax_output = Activation('softmax', name='softmax_output')(logits)

model = Model(inputs=input_tensor, outputs=[logits_variance,softmax_output])

return modelThe trainable part of my model is two sets of BatchNormalization, Dropout, Dense, and relu layers on top of the ResNet50 output. The logits and variance are calculated using separate Dense layers. Note that the variance layer applies a softplus activation function to ensure the model always predicts variance values greater than zero. The logit and variance layers are then recombined for the aleatoric loss function and the softmax is calculated using just the logit layer.

model.compile(

optimizer=Adam(lr=1e-3, decay=0.001),

loss={

'logits_variance': bayesian_categorical_crossentropy(100, 10),

'softmax_output': 'categorical_crossentropy'

},

metrics={'softmax_output': metrics.categorical_accuracy},

loss_weights={'logits_variance': .2, 'softmax_output': 1.})I trained the model using two losses, one is the aleatoric uncertainty loss function and the other is the standard categorical cross entropy function. This allows the last Dense layer, which creates the logits, to learn only how to produce better logit values while the Dense layer that creates the variance learns only about predicting variance. The two prior Dense layers will train on both of these losses. The aleatoric uncertainty loss function is weighted less than the categorical cross entropy loss because the aleatoric uncertainty loss includes the categorical cross entropy loss as one of its terms.

I used 100 Monte Carlo simulations for calculating the Bayesian loss function. It took about 70 seconds per epoch. I found increasing the number of Monte Carlo simulations from 100 to 1,000 added about four minutes to each training epoch.

I added augmented data to the training set by randomly applying a gamma value of 0.5 or 2.0 to decrease or increase the brightness of each image. In practice I found the cifar10 dataset did not have many images that would in theory exhibit high aleatoric uncertainty. This is probably by design. By adding images with adjusted gamma values to images in the training set, I am attempting to give the model more images that should have high aleatoric uncertainty.

Example image with gamma value distortion. 1.0 is no distortion

Unfortunately, predicting epistemic uncertainty takes a considerable amount of time. It takes about 2-3 seconds on my Mac CPU for the fully connected layers to predict all 50,000 classes for the training set but over five minutes for the epistemic uncertainty predictions. This isn't that surprising because epistemic uncertainty requires running Monte Carlo simulations on each image. I ran 100 Monte Carlo simulations so it is reasonable to expect the prediction process to take about 100 times longer to predict epistemic uncertainty than aleatoric uncertainty.

Lastly, my project is setup to easily switch out the underlying encoder network and train models for other datasets in the future. Feel free to play with it if you want a deeper dive into training your own Bayesian deep learning classifier.

Example of each class in cifar10

My model's categorical accuracy on the test dataset is 86.4%. This is not an amazing score by any means. I was able to produce scores higher than 93%, but only by sacrificing the accuracy of the aleatoric uncertainty. There are a few different hyperparameters I could play with to increase my score. I spent very little time tuning the weights of the two loss functions and I suspect that changing these hyperparameters could greatly increase my model accuracy. I could also unfreeze the Resnet50 layers and train those as well. While getting better accuracy scores on this dataset is interesting, Bayesian deep learning is about both the predictions and the uncertainty estimates and so I will spend the rest of the post evaluating the validity of the uncertainty predictions of my model.

Figure 5: uncertainty mean and standard deviation for test set

The aleatoric uncertainty values tend to be much smaller than the epistemic uncertainty. These two values can't be compared directly on the same image. They can however be compared against the uncertainty values the model predicts for other images in this dataset.

Figure 6: Uncertainty to relative rank of 'right' logit value.

To further explore the uncertainty, I broke the test data into three groups based on the relative value of the correct logit. In Figure 5, 'first' includes all of the correct predictions (i.e logit value for the 'right' label was the largest value). 'second', includes all of the cases where the 'right' label is the second largest logit value. 'rest' includes all of the other cases. 86.4% of the samples are in the 'first' group, 8.7% are in the 'second' group, and 4.9% are in the 'rest' group. Figure 5 shows the mean and standard deviation of the aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty for the test set broken out by these three groups. As I was hoping, the epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties are correlated with the relative rank of the 'right' logit. This indicates the model is more likely to identify incorrect labels as situations it is unsure about. Additionally, the model is predicting greater than zero uncertainty when the model's prediction is correct. I expected the model to exhibit this characteristic because the model can be uncertain even if it's prediction is correct.

Images with highest aleatoric uncertainty

Images with the highest epistemic uncertainty

Above are the images with the highest aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty. While it is interesting to look at the images, it is not exactly clear to me why these images images have high aleatoric or epistemic uncertainty. This is one downside to training an image classifier to produce uncertainty. The uncertainty for the entire image is reduced to a single value. It is often times much easier to understand uncertainty in an image segmentation model because it is easier to compare the results for each pixel in an image.

"Illustrating the difference between aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty for semantic segmentation. You can notice that aleatoric uncertainty captures object boundaries where labels are noisy. The bottom row shows a failure case of the segmentation model, when the model is unfamiliar with the footpath, and the corresponding increased epistemic uncertainty." link

If my model understands aleatoric uncertainty well, my model should predict larger aleatoric uncertainty values for images with low contrast, high brightness/darkness, or high occlusions To test this theory, I applied a range of gamma values to my test images to increase/decrease the pixel intensity and predicted outcomes for the augmented images.

Figure 7: Left side: Images & uncertainties with gamma values applied. Right side: Images & uncertainties of original image.

The model's accuracy on the augmented images is 5.5%. This means the gamma images completely tricked my model. The model wasn't trained to score well on these gamma distortions, so that is to be expected. Figure 6 shows the predicted uncertainty for eight of the augmented images on the left and eight original uncertainties and images on the right. The first four images have the highest predicted aleatoric uncertainty of the augmented images and the last four had the lowest aleatoric uncertainty of the augmented images. I am excited to see that the model predicts higher aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties for each augmented image compared with the original image! The aleatoric uncertainty should be larger because the mock adverse lighting conditions make the images harder to understand and the epistemic uncertainty should be larger because the model has not been trained on images with larger gamma distortions.

The model detailed in this post explores only the tip of the Bayesian deep learning iceberg and going forward there are several ways in which I believe I could improve the model's predictions. For example, I could continue to play with the loss weights and unfreeze the Resnet50 convolutional layers to see if I can get a better accuracy score without losing the uncertainty characteristics detailed above. I could also try training a model on a dataset that has more images that exhibit high aleatoric uncertainty. One candidate is the German Traffic Sign Recognition Benchmark dataset which I've worked with in one of my Udacity projects. This dataset is specifically meant to make the classifier "cope with large variations in visual appearances due to illumination changes, partial occlusions, rotations, weather conditions". Sounds like aleatoric uncertainty to me!

In addition to trying to improve my model, I could also explore my trained model further. One approach would be to see how my model handles adversarial examples. To do this, I could use a library like CleverHans created by Ian Goodfellow. This library uses an adversarial neural network to help explore model vulnerabilities. It would be interesting to see if adversarial examples produced by CleverHans also result in high uncertainties.

Another library I am excited to explore is Edward, a Python library for probabilistic modeling, inference, and criticism. Edward supports the creation of network layers with probability distributions and makes it easy to perform variational inference. This blog post uses Edward to train a Bayesian deep learning classifier on the MNIST dataset.

If you've made it this far, I am very impressed and appreciative. Hopefully this post has inspired you to include uncertainty in your next deep learning project.