Table of contents

Source:

- https://codeburst.io/why-goroutines-are-not-lightweight-threads-7c460c1f155f

- https://medium.com/@riteeksrivastava/a-complete-journey-with-goroutines-8472630c7f5c

- A thread is just a sequence of instructions that can be executed independently by a processor.

- Modern processors can executed multiple threads at once (multi-threading) and also switch between threads to achieve parallelism.

- Threads share memory and don't need to create a new virtual memory space when they are created and thus don't require a MMU context switch.

- Communication between threads is simpler as they have a shared memory while processes requires various modes of IPC (Inter-Process Communications) like semaphores, messages queues, pipes etc.

- Things make threads slow:

- Threads consume a lot of memory due to their large stack size (>= 1MB).

- Threads need to restore a lot registers some of which include AVX, SSE, PC, SP (???) which hurts the application performance.

- Threads setup and teardown requires call to OS for resources (such as memory) which is slow.

- Threads are scheduled preemptively: If a process is running for more than a scheduler time slice, it would prempt the process and schedule execution of another runnable process on the same CPU), the scheduler needs to save/restore all register.

- The idea of Goroutines was inspired by Coroutines.

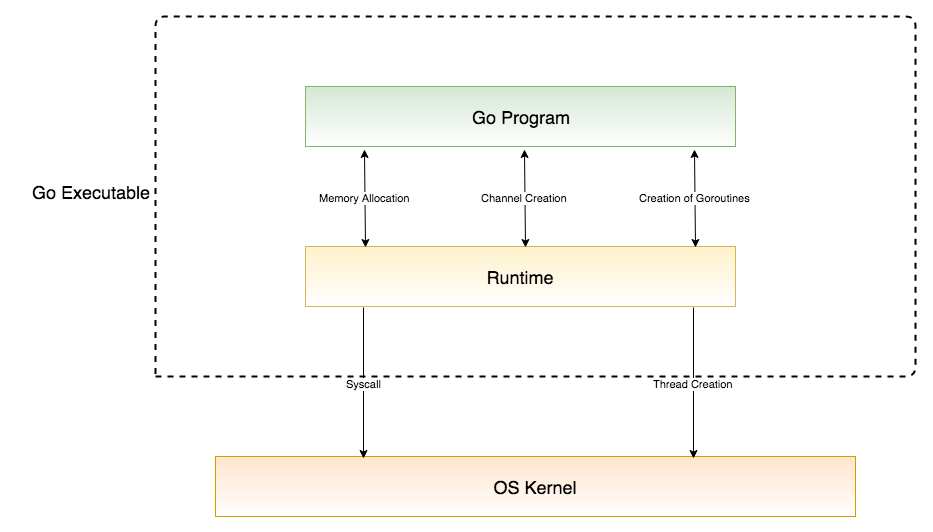

- Goroutines exists only in the virtual space of Go runtime and not in the OS. Hence, a Go runtime scheduler is needed which manages their lifecycle.

- On startup, Go runtime starts a number of goroutines for GC, scheduler and user code (3 structs: G struct, M struct and Sched struct). An OS thread is created to handle these goroutines. These threads can be at most equal to GOMAXPROCS.

- Goroutines are multiplexed onto multiple OS threads so if one should block, such as while waiting for I/O, others continue to run. Their design hides many of the complexities of thread creation and management.

- A goroutine is created with initial only 2KB of stack size.

- Goroutines are scheduled cooperatively, they do not directly talk to the OS kernel. When a Goroutine switch occurs, very few registers like program counter and stack pointer need to be saved/restored.

Source: https://medium.com/@stev3npy/go-concurrency-why-not-1b3b60a47634

// Simple goroutine

go func() {

fmt.Println("Hello from goroutine!")

}()- Passing parameters:

- Create a new value for each goroutine: Passing parameters directly ensures that each goroutine receives its own independent copy of the values, rather than referencing shared variables.

- Avoid closure-related issue: When using closures, variables captured by goroutine may change before the goroutine runs, leading to unexpected results.

- Ensure safe concurrency: Each goroutine operates with its own copy of the parameters, reducing the risk of data races or unintended modifications in concurrent operations.

// Goroutine with parameters

go func(msg string, id int) {

fmt.Printf("Message %d: %s\n", id, msg)

}("Hello", 1)- Goroutine with proper cleanup:

- Provide controlled shutdown mechanism: Using a context with cancellation allows for graceful shutdown of goroutines, ensuring they exit cleanly when needed.

- Prevent goroutine leaks: Without proper cancellation, goroutines might continue running in the background even after they are no longer needed, consuming resources. This pattern helps avoid such leaks.

- Ensure resource cleanup: By canceling the context and monitoring

ctx.Done(), you can ensure that any resources allocated during the goroutine's execute properly cleaned up when the goroutine finishes. - Context propagates cancellation: The context allows cancellation to propagate through multiple goroutines, ensuring that all dependent goroutines are informed of the cancellation and can terminate properly.

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

defer cancel() // Important: ensures cleanup

go func(ctx context.Context) {

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

fmt.Println("Cleanup and exit")

return

default:

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}

}

}(ctx)

// It run's for 5 seconds

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

} // Context cancellation happens here due to defer- A WaitGroup allows you to wait for a group of goroutines to complete their execution.

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Launch multiple workers

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1) // Must be called before the goroutine starts

go func(id int) {

defer wg.Done() // Ensures Done is called even if a panic occurs

fmt.Printf("Worker %d doing work\n", id)

}(i)

}

wg.Wait() // Blocks until all workers are done

}-

Key points:

- Add() must be called before the goroutine starts.

- Done() should be deferred to handle panics.

- Wait() blocks until the counter reaches zero.

- The counter must never go negative.

-

Advanced work pool:

- Bounded concurrency: By fixing the number of workers (numWorkers), you control the level of concurrency, ensuring that you prevent overwhelming system resources with too many goroutines.

- Efficient resource utilization: Using a buffered channel for jobs and results allows workers to process jobs concurrently and prevents them from waiting on one another unnecessarily.

- Prevents system overload: By controlling the number of workers, you manage resource consumption efficiently, avoiding spikes in CPU or memory usage.

- Proper cleanup through channel closing: Closing channels after jobs and workers are done ensures that no goroutines are left hanging, preventing potential resource leaks.

- Clear separation of concerns: The worker function focuses solely on processing jobs and reporting results, while the pool manager handles job distribution and result collection, ensuring a clean and maintainable design.

type Job struct {

ID int

Data string

}

type Result struct {

JobID int

Processed string

Error error

}

func WorkerPool(jobs []Job, numWorkers int) []Result {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

jobsChan := make(chan Job, len(jobs)) // Buffered channel for jobs

resultsChan := make(chan Result, len(jobs)) // Buffered channel for results

// Start workers

for i := 0; i < numWorkers; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go worker(&wg, jobsChan, resultsChan)

}

// Send jobs

go func() {

for _, job := range jobs {

jobsChan <- job

}

close(jobsChan) // Close after all jobs are sent

}()

// Wait and collect results

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(resultsChan) // Close after all workers are done

}()

// Collect results

var results []Result

for result := range resultsChan {

results = append(results, result)

}

return results

}

func worker(wg *sync.WaitGroup, jobs <-chan Job, results chan<- Result) {

defer wg.Done()

for job := range jobs {

// Process job

result := Result{

JobID: job.ID,

Processed: processJob(job), // processing logic

}

results <- result

}

}- A channel in Go is a communication mechanism that allows goroutines to safely share data.

// Unbuffered channel

ch := make(chan string)

// Blocks until receiver is ready

// Used for synchronization

// Buffered channel

bufferedCh := make(chan string, 5)

// Blocks only when buffer is full

// Used for async communication with known bounds

// Read-only (receive-only) channel

func readOnly(ch <-chan string) {

// Can only read from ch

}

// Write-only (send-only) channel

func writeOnly(ch chan<- string) {

// Can only write to ch

}

// Bidirectional channel

func biDirectional(ch chan string) {

// Can used for both sending and receiving

}- Select pattern:

- Non-blocking handling of multiple channels: The select statement enables the function to wait for multiple channels at once, ensuring non-blocking handling of incoming data.

- Graceful handling of closed channels: When a channel is closed, setting it to nil removes it from future select cases, preventing errors from repeated reads on a closed channel.

- Timeout mechanism: The time.After channel enforces a timeout, ensuring the function returns if no messages arrive within the specified duration.

- Context cancellation support: The

ctx.Done()case respects external cancellation signals, providing controlled shutdown and resource cleanup. - Avoids goroutine leaks: Proper handling of timeouts and context cancellation prevents goroutines from running indefinitely, avoiding potential memory and resource leaks.

func handleMultipleChannels(

ctx context.Context,

ch1, ch2 <-chan string,

timeout time.Duration,

) (string, error) {

timeoutCh := time.After(timeout)

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return "", ctx.Err() // Handles context cancellation

case msg1, ok := <-ch1:

if !ok {

// Channel closed

ch1 = nil // // Disable this case to prevent repeated selects on a closed channel

continue

}

return fmt.Sprintf("Ch1: %s", msg1), nil

case msg2, ok := <-ch2:

if !ok {

ch2 = nil

continue

}

return fmt.Sprintf("Ch2: %s", msg2), nil

case <-timeoutCh:

return "", fmt.Errorf("timeout after %v", timeout)

}

}

}- Fan-Out Fan-In pattern:

- Fan-Out (Parallel Processing): The

fanOutfunction distributes tasks across multiple worker goroutines, enabling concurrent processing. Each worker independently processes items from theinputchannel using the providedprocessorfunction. - Fan-In (Result Merging): The

fanInfunction consolidates the output from multiple workers into a singlemergedchannel, making it easier for downstream functions to handle the results. - Contextual Cancellation: By passing a ctx into both

fanOutandfanIn, the pattern respects cancellation signals, ensuring all workers and the fan-in process terminate gracefully when cancellation is requested. - Generic Reusability: With generics (

T any), thefanOut,fanIn, and worker functions are versatile and can handle different data types, making the implementation reusable across various use cases. - Efficient Resource Cleanup: The pattern ensures that channels are closed after processing, preventing resource leaks and ensuring proper resource management.

- Non-blocking Channels: Each channel operation (

input,output, andmerged) usesselectwith a case for context cancellation, enabling non-blocking communication and preventing deadlocks.

- Fan-Out (Parallel Processing): The

// Fan-Out function

func fanOut[T any](

ctx context.Context,

input <-chan T,

numWorkers int,

processor func(T) T,

) []<-chan T {

outputs := make([]<-chan T, numWorkers)

for i := 0; i < numWorkers; i++ {

outputs[i] = worker(ctx, input, processor)

}

return outputs

}

// Worker function

func worker[T any](

ctx context.Context,

input <-chan T,

processor func(T) T,

) <-chan T {

output := make(chan T)

go func() {

defer close(output)

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case val, ok := <-input:

if !ok {

return

}

select {

case output <- processor(val):

case <-ctx.Done():

return

}

}

}

}()

return output

}

// Fan-In function

func fanIn[T any](

ctx context.Context,

channels ...<-chan T,

) <-chan T {

merged := make(chan T)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Merge function for each channel

merge := func(ch <-chan T) {

defer wg.Done()

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case val, ok := <-ch:

if !ok {

return

}

select {

case merged <- val:

case <-ctx.Done():

return

}

}

}

}

wg.Add(len(channels))

for _, ch := range channels {

go merge(ch)

}

// Close merged channel after all inputs are done

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(merged)

}()

return merged

}- When dealing with long-running or resource-intensive tasks, managing timeouts and cancellations is key to using resources efficiently and avoiding issues like goroutine leaks. Here’s a how to set up a timeout pattern with context and handle cancellation gracefully.

- Prevents Goroutine Leaks: The

ctx.Done()case ensures goroutines exit cleanly if the context is canceled, so you don’t end up with orphaned goroutines consuming memory. - Implements Proper Timeouts: By using a WithTimeout context, you control how long each operation can take, improving system responsiveness.

- Graceful Cancellation Handling: The

ctx.Done()check ensures that operations stop if they’re no longer needed, especially when part of a larger, nested workflow. - Error Propagation: This pattern uses buffered channels for error handling, allowing you to handle errors independently and preventing goroutines from blocking on send.

- Prevents Goroutine Leaks: The

func operationWithTimeout(

parentCtx context.Context,

duration time.Duration,

) (string, error) {

// Create a context with a timeout

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(parentCtx, duration)

defer cancel() // Always defer cancel to free up resources

return doOperation(ctx)

}

func doOperation(ctx context.Context) (string, error) {

resultCh := make(chan string, 1)

errCh := make(chan error, 1)

go func() {

// Simulate a long-running or expensive operation

result, err := expensiveOperation()

// Send result or error based on context state

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return // Stop work if context is canceled

case resultCh <- result:

if err != nil {

errCh <- err

}

}

}()

// Await results or handle cancellation

select {

case result := <-resultCh:

return result, <-errCh

case <-ctx.Done():

return "", ctx.Err() // Return the context error if canceled

}

}- Safe counter:

- Safe Concurrent Access: The mutex (

mu) ensures that only one goroutine can update count at a time. This prevents data corruption and guarantees thread safety when accessing shared data. - Efficient Read-Write Locking: The use of

sync.RWMutexallows;RLockfor reads allows multiple concurrent readers, boosting performance when multiple goroutines only need to check the value.Lockfor writes is exclusive, ensuring only one writer at a time, which is critical for maintaining correct counts. - Automatic Cleanup with defer: By using

defer, we ensure that the lock is released when the function finishes, even if it exits early. This helps prevent deadlocks and keeps the code clean. - Encapsulation of State: The

Counterstruct and its methods hide the synchronization details from the caller and reducing the chance of misuse.

- Safe Concurrent Access: The mutex (

type Counter struct {

mu sync.RWMutex

count map[string]int

}

func NewCounter() *Counter {

return &Counter{

count: make(map[string]int),

}

}

func (c *Counter) Increment(key string) {

c.mu.Lock()

defer c.mu.Unlock()

c.count[key]++

}

func (c *Counter) Get(key string) int {

c.mu.RLock()

defer c.mu.RUnlock()

return c.count[key]

}- Rate limiter:

- Controlled Throughput:

tokensis a buffered channel that limits operations to the number of tokens in it. Each request consumes one token, enforcing the limit. - Periodic Refills: The

goroutine uses atickerto refill the bucket at the defined interval. - Efficiency: Non-blocking select (

defaultcase) prevents the go routine from waiting if the tokens bucket is already full, ensuring memory efficiency.

- Controlled Throughput:

type RateLimiter struct {

tokens chan struct{}

interval time.Duration

}

func NewRateLimiter(rate int, interval time.Duration) *RateLimiter {

rl := &RateLimiter{

tokens: make(chan struct{}, rate),

interval: interval,

}

// Fill token bucket

for i := 0; i < rate; i++ {

rl.tokens <- struct{}{}

}

// Refill tokens periodically

go func() {

ticker := time.NewTicker(interval)

defer ticker.Stop()

for range ticker.C {

select {

case rl.tokens <- struct{}{}:

default: // Don't block if tokens channel is full

}

}

}()

return rl

}

func (rl *RateLimiter) Wait() {

<-rl.tokens

}- Circuit Breaker:

- Controlled Failure Handling: If a service fails repeatedly,

isOpenprevents further calls. This reduces load on the service and avoids predictable failures. - Threshold and Reset Logic: The circuit “trips” if

failureCountexceeds threshold. The breaker then rechecks theresetTimeoutbefore allowing another call, minimizing downtime. - Efficient Synchronization: The combination of

RLockfor reading states andLockfor writing states in thecanExecuteandrecordResultmethods prevents race conditions and improves performance.

- Controlled Failure Handling: If a service fails repeatedly,

type CircuitBreaker struct {

mu sync.RWMutex

failureCount int

threshold int

resetTimeout time.Duration

lastFailureTime time.Time

isOpen bool

}

func NewCircuitBreaker(threshold int, resetTimeout time.Duration) *CircuitBreaker {

return &CircuitBreaker{

threshold: threshold,

resetTimeout: resetTimeout,

}

}

func (cb *CircuitBreaker) Execute(operation func() error) error {

if !cb.canExecute() {

return fmt.Errorf("circuit breaker is open")

}

err := operation()

cb.recordResult(err)

return err

}

func (cb *CircuitBreaker) canExecute() bool {

cb.mu.RLock()

defer cb.mu.RUnlock()

if !cb.isOpen {

return true

}

// Check reset timeout

if time.Since(cb.lastFailureTime) > cb.resetTimeout {

cb.mu.RUnlock()

cb.mu.Lock()

cb.isOpen = false

cb.failureCount = 0

cb.mu.Unlock()

cb.mu.RLock()

return true

}

return false

}

func (cb *CircuitBreaker) recordResult(err error) {

cb.mu.Lock()

defer cb.mu.Unlock()

if err != nil {

cb.failureCount++

cb.lastFailureTime = time.Now()

if cb.failureCount >= cb.threshold {

cb.isOpen = true

}

} else {

cb.failureCount = 0

cb.isOpen = false

}

}- The Error Group Pattern enables concurrent processing with error propagation, ensuring that if one goroutine fails, the entire operation can be canceled gracefully. This is especially useful when multiple items or tasks need parallel processing, and error handling must be centralized.

- Centralized Error Handling:

errgroup.WithContext(ctx)coordinates all goroutines, allowing any encountered error to cancel all tasks. If any goroutine fails,g.Wait()will return the error. - Controlled Concurrency:

g.Golaunches each goroutine witherrgroup, reducing boilerplate code for error handling. - Channel-Based Results Processing:

resultschannel stores successful items and is closed after all tasks finish, preventing deadlocks by gracefully shutting down. - Ensured Closure Safety: Creating a new

itemvariable inside the loop prevents closure data race issues, ensuring each goroutine has a unique item. `

- Centralized Error Handling:

func processItems(ctx context.Context, items []string) error {

// Initialize an error group with context for managing goroutines and errors.

g, ctx := errgroup.WithContext(ctx)

results := make(chan string, len(items))

for _, item := range items {

item := item // Create new variable for closure to avoid data race

g.Go(func() error {

// Check if context was canceled

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err() // Propagate cancellation error

default:

if err := processItem(item); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("processing %s: %w", item, err) // Capture specific item error

}

results <- item

return nil

}

})

}

// Closing results channel when all goroutines complete

go func() {

g.Wait()

close(results)

}()

for result := range results {

fmt.Printf("Processed: %s\n", result)

}

// Return any error encountered during processing

return g.Wait()

}- Always use context for cancellation.

// ❌ Bad: No cancellation mechanism

func longRunningTask() error {

for {

// Do work

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}

}

// ✅ Good: Cancellable operation

func longRunningTask(ctx context.Context) error {

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err()

default:

// Do work

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}

}

}- Proper channel closing: channels should be closed only by the sender.

// ❌ Bad: Closing channel from receiver

func bad() {

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

val := <-ch

close(ch) // Wrong: receiver closing channel

}()

ch <- 1

}

// ✅ Good: Sender owns channel closure

func good() {

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(ch) // Right: sender closes

ch <- 1

}()

<-ch

}- Proper error handling:

// ❌ Bad: Lost errors

func badErrorHandling(tasks []Task) {

for _, task := range tasks {

go func(t Task) {

err := process(t)

if err != nil {

// Error lost!

fmt.Println(err)

}

}(task)

}

}

// ✅ Good: Error collection

func goodErrorHandling(tasks []Task) error {

errCh := make(chan error, len(tasks))

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for _, task := range tasks {

wg.Add(1)

go func(t Task) {

defer wg.Done()

if err := process(t); err != nil {

errCh <- err

}

}(task)

}

// Wait in separate goroutine

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(errCh)

}()

// Collect errors

var errs []error

for err := range errCh {

errs = append(errs, err)

}

if len(errs) > 0 {

return fmt.Errorf("multiple errors: %v", errs)

}

return nil

}- Goroutine leaks:

// ❌ Bad: Leaking goroutine

func leakyGoroutine() {

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

val := <-ch // Goroutine stuck forever

fmt.Println(val)

}()

// Channel never receives value, goroutine leaks

}

// ✅ Good: Prevent leaks with context

func noLeak(ctx context.Context) {

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

select {

case val := <-ch:

fmt.Println(val)

case <-ctx.Done():

return // Clean exit

}

}()

}- Race conditions:

// ❌ Bad: Race condition

type Counter struct {

count int

}

func (c *Counter) Increment() {

c.count++ // Race condition!

}

// ✅ Good: Use sync/atomic

type Counter struct {

count atomic.Int64

}

func (c *Counter) Increment() {

c.count.Add(1) // Atomic operation

}- Mutex copying: When embedding mutexes, always use pointer receivers to prevent accidental copying.

// ❌ Bad: Copying mutex

type Config struct {

sync.Mutex

data map[string]string

}

func (c Config) Get(key string) string { // Mutex copied!

c.Lock()

defer c.Unlock()

return c.data[key]

}

// ✅ Good: Pointer receiver

type Config struct {

mu sync.Mutex

data map[string]string

}

func (c *Config) Get(key string) string { // Pointer receiver

c.mu.Lock()

defer c.mu.Unlock()

return c.data[key]

}- Channel size: Choose buffer sizes based on specific use cases to avoid deadlocks or inefficiency.

// ❌ Bad: Arbitrary buffer size

ch := make(chan int, 100) // Why 100?

// ✅ Good: Buffer size matches use case

// For known number of items:

ch := make(chan int, len(items))

// For rate limiting:

ch := make(chan struct{}, workerCount)

// For latest value only:

ch := make(chan int, 1)- Use

sync.Poolfor Frequently Allocated Objects like buffers or temporary structs. This reduces the frequency of allocations and reuses objects instead.

var bufferPool = sync.Pool{

New: func() interface{} {

return new(bytes.Buffer)

},

}

func processData(data []byte) error {

buf := bufferPool.Get().(*bytes.Buffer)

defer func() {

buf.Reset()

bufferPool.Put(buf)

}()

// Example of using buffer for processing

buf.Write(data)

// Do more work with buf...

return nil

}- Consider Atomic operations for simple counters: Atomic operations are faster than using mutexes for simple counter updates and are safe in concurrent environments.

var counter atomic.Int64

func incrementCounter() {

counter.Add(1)

}

func getCounter() int64 {

return counter.Load()

}- Profile before optimizing: Use Go’s built-in

pprofpackage to gather CPU and memory profiles before optimizing your code. Profiling identifies bottlenecks accurately so you can focus on areas that need optimization. - Use buffered channels when message count is known:

func processItems(items []int) {

ch := make(chan int, len(items)) // Buffered channel

for _, item := range items {

ch <- item

}

close(ch)

for item := range ch {

fmt.Println("Processing:", item)

}

}- Implement proper cleanup for long-running goroutines:

func longRunningTask(ctx context.Context) {

ticker := time.NewTicker(time.Second)

defer ticker.Stop() // Ensure ticker is cleaned up

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

fmt.Println("Cleanup and exit")

return // Exit goroutine on context cancellation

case <-ticker.C:

// Simulate periodic work

fmt.Println("Working...")

}

}

}

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 5*time.Second)

defer cancel() // Clean up context after done

go longRunningTask(ctx)

time.Sleep(6 * time.Second) // Wait to observe cancellation

}