OpenBazaar is a marketplace platform compromised of the following components:

- The Kademlia-style Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Network

- The network architecture governing peer-to-peer connections

- The Trade Protocol

- The fundamental rules governing the type trade between peers

- The Application

- How a users access the network and executes the trades protocol

Users download the OpenBazaar application to access the network and execute the trade protocol with other users on the network.

The OpenBazaar network is the backbone of the project. It is designed to be scalable, supporting millions of people finding goods and services offered by fellow peers, who could be located anywhere in the world.

The Kademlia-style architecture theoretically supports this vision, and has a track-record of connecting millions of peers as demonstrated by BitTorrent. The chief engineering difficulty of building OpenBazaar historically has been implementing this component.

The Kademlia-style P2P network is older and distinct from the Bitcoin blockchain. To create a node, a network identity or global unique identifier (GUID) needs to be created. Firstly, random number is generated between a range of 1 to 2256 to obtain a private key. From this key, a public key is derived.

The public key is then digitally signed with the the private key (self-signature) and sha256 hashed. The resulting hex is then further hashed by RIPEMD160 to generate the GUID. This GUID is impossible to forge or spoof without compromising the private key, and is the basis of a node's pseudonymous identity on the network.

GUID = RIPEMD160(SHA256(self_signed pubkey))

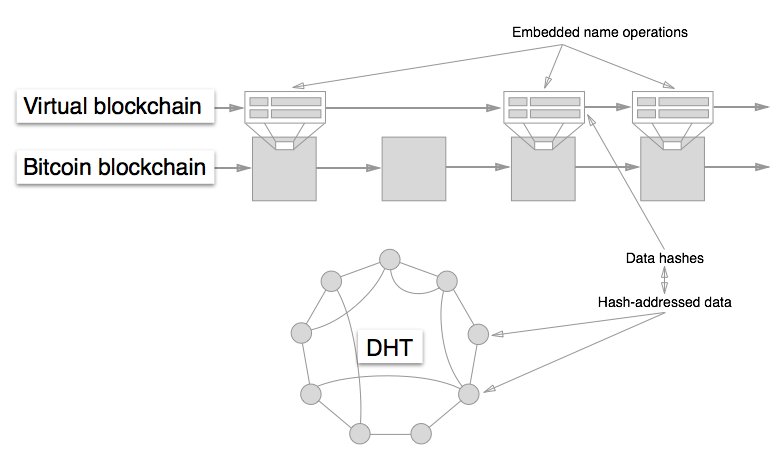

The GUID is mapped to your dynamic IP address and port on a distributed hash table (DHT). This is not a distributed ledger like the blockchain, but a local 'map' of GUIDs (peers) and their IP addresses in your 'bucket' ('bucket' defined as similar GUIDs within a defined range). Each peer's DHT allows anyone on the network to find the location of a specific peer in only a few hops (i.e. think 6 degrees of separation). On this basis, peers can connect to each other to exchange data.

The network allows for a GUID to be associated with more than just an IP address, but other attribute-value pairs that can be searched (i.e. decentralized search).

In OpenBazaar, the DHT lists GUID hashes of contracts that the a peer (GUID) is selling and keywords that are associated with that contract. This enables other peers to decentrally search the network for specific contracts by their hash and/or keyword, compiling a list of relevant hits and their corresponding GUIDs. The user can then select the peer and directly access their store to commence trade.

The overall features of this architecture are:

- Minimal resources are required to run an OpenBazaar node (relative to Bitcoin)

- Scalable to millions of users

- Uses Bitcoin only as a currency for decentralised trade

- Contracts (listings) are hosted on the merchant's node.

- Enables rapid listings, as distributed consensus isn't required to list goods/services

This design does have some drawbacks, which third party services (or future technological innovation) can address:

- Nodes are required to remain online for listings to be accessible by peers

- The project is exploring using the DHT as a temporary cache for listing contracts and placing asynchronous encrypted orders

- Nodes can be targeted (hackers, spammers, governments) on the basis of what they are listing, although the marketplace and protocol remain censorship-resistant

Presently, both TCP/IP AND rUDP are used to to make connections between peers. The rUDP-based connections tend to overcome NATs (network address translation) and other obstacles preventing peers from accessing the network, and thus avoiding complicated port forwarding requirements beyond the skills of most users. This also means that these connections cannot be easily used through TOR to obfuscate the true IP address of a node.

The trade protocol describes a set of fundamental rules that govern decentralised trade on OpenBazaar between two or more trading partners.

The protocol is made up of two major sub-components:

- Bitcoin Payments and Escrow

- Payment with Bitcoin

- Escrow selection

- Ricardian Contracts

- Formalizes the terms of trade

All trade over OpenBazaar exclusively uses Bitcoin. OpenBazaar will support four payment options with Bitcoin:

- Direct payment

- Alice transfers bitcoin to Bob in a simple payment

- Double-deposit 'MAD' escrow

- Alice and Bob create a 2-of-2 multisignature escrow address

- Alice and Bob need to agree to release funds from that address

- Notary escrow

- Alice, Bob, and Charlie (a third party 'notary') create a 2-of-3 multisignature escrow address

- Two members of this party are required to release funds from the address

- Notary pooled escrow

- Alice, Bob, and others (multiple third party notaries) create a n-of-m multisignature escrow address

- Multiple parties from the pool of notaries are required to release funds from the address

Hierachical Deterministic Wallets

Irrespective of the payment option selected, individual bitcoin pubkeys are derived from a hierarchical deterministic (HD) seed to avoid address reuse and efficiently manage the signing keys. All signing keys can be recovered from the seed if the node is inadvertently destroyed or lost.

Of the three payments options, direct payment and MAD escrow have no enforceable dispute resolution mechanism and zero redundancy if keys are lost. However, their use in OpenBazaar is appropriate in following scenarios:

- Direct payment from well-established merchants and with high reputation; presumption is that the buyer possesses a high degree of trust to the merchant.

- MAD escrow between two parties who want to transact directly without any third party involvement, but do not share a high degree of trust. These users are assumed to have an above average level of technical skill to manage risks such as key loss or incapacitation, and who have a firm understanding of the implications of a failed trade.

Multisignature transactions used are for notary escrow payments, which enable an innovative form of multiparty escrow. Rather than funds being send into the exclusive custody of a trusted third party, funds are sent to an address that are not in the exclusive custody of any individual. The multisignature address is generated by comining the unique bitcoin pubkeys from the merchant, buyer, and notary. To release funds, cooperation (in the form of digital signatures) between two of the three participants is required. A higher level description of multisignature transactions can be found in the Bitcoin documentation. The overall effect of this system avoids a situation where one party in the trade can run away with the funds. The third party keyholder in these payments is called a notary. The role of a notary is further described below.

While theoretically other crypto-currencies can be supported in the core code, provided they follow a similar specification to Bitcoin multisignature transactions, altcoin implementations will not be pursed. Third party services (e.g. Shapeshift.io) can be used to either:

- Convert altcoins into bitcoin to fund the multiparty escrow address

- Convert bitcoins to altcoins when funds are released from multiparty escrow.

In this model, Bitcoin is being used as the 'backend' transactional currency, while altcoins are used as an onramp and/or offramp from Bitcoin escrow via these exchanges.

Similar to altcoins, fiat payments may be supported using third party services to convert fiat currencies into Bitcoin to fund multisignature escrow addresses, or automatically convert bitcoin payout funds to fiat currency of the merchant's choice.

Role of Third Party Exchanges

A Ricardian Contract can be defined as a single document that is a) a contract offered by an issuer to holders, b) for a valuable right held by holders, and managed by the issuer, c) easily readable by people (like a contract on paper), d) readable by programs (parsable like a database), e) digitally signed, f) carries the keys and server information, and g) allied with a unique and secure identifier.

- Ian Grigg

Ricardian contracts (RC) are digital documents that record an agreement between multiple parties, which are signed and cryptographically verified, and formatted to be human and machine-readable. The one-way hash of RC establish a tamper-proof receipt of the terms and conditions of a trade, which eliminates potential disputes that may arise from hearsay claims between counterparties.

To be 'machine readable', the terms and conditions are formatted in JSON with a hierarchy of attribute-value pairs: the contract schema. As there are multiple types of trade that OpenBazaar aims to support, each will have its own contract schema. Common to all schemas are four modules:

- Metadata module

- ID module

- Trade module

- Ledger module

Ricardian contracts in OpenBazaar will typically have one metadata, trade and ledger module. Multiple ID modules are required to represent each party in the trade (at least 1 merchant, buyer, and notary).

The metadata module is the header of the RC and informs users and the app what type of trade will take place and the period of time the contract is valid.

The ID module contains the necessary identifying data for a peer on the network. It will contain the following types of ID:

- Network ID (minimum ID required for a trade)

- GUID (global unique identifier)

- Unique network identifier

- One GUID per node on the network

- Bitcoin pubkey

- Used to create/sign multisignature escrow address

- Generated from HD seed

- One key per contract

- PGP pubkey

- Used to sign contracts

- Establishes a 'mobile' identity

- Multiple nodes can provably belong to 1 PGP key

- GUID (global unique identifier)

- Passcard ID

- Passcard - Digital identity as per the 'Blockchain Name System'

- Links to email and other communication channels

- Verified links to social networking platforms

- Passcard - Digital identity as per the 'Blockchain Name System'

- Legally accessible ID

- Contact details that are verified by a third party (think certificate authorities), which basically verifies that this identity is legally accessible in the event of some dispute that needs to be resolved in court

For the purposes a basic trade, only the pseudonymous identity is required. Unlike traditional e-commerce platforms, neither the meatspace or legally accessible identities are required for trade. This point is as much about maintaining privacy as it is about supporting trade for jurisdictions that lack infrastructure to support ID verification.

The trade module contains the necessary semantic data to define the good or service to be traded for bitcoin. The structure of this module will vary depending on the type of good or service to be traded. As a result, we will pursue community engagement to evolve categories, standards and templates.

The ledger module of the Ricardian contract traces the various stages of the trade between the parties involved. The structure of the ledger will dictate the signing order. The ledger module is read by the client/app, which enforces signing and forwarding of the contract to the next appropriate party. The final product is a contract that has a completed signing order and transaction history to act as a tamper-proof trade receipt. The structure of the ledger module will also vary according to the type of good and service to be traded for bitcoin.

The ledger is formatted according to the step-by-step stages where data and signatures are required from each participating party. As a platform, users will be able to design custom Ricardian contracts with unique signing orders to support new types of markets.

{

"01_merchant": {

"01_listing": {

"01_metadata": {

"01_obcv": "",

"02_expiry": "",

"03_category": "physical good",

"04_category_sub": "fixed price",

"05_order_flow": [

"merchant",

"buyer",

"merchant",

"buyer"

]

},

"02_id": {

"01_guid": "",

"02_pubkeys": {

"bitcoin": "",

"pgp": ""

},

"03_handle": "",

"04_passcard": "",

"05_contact": {

"bitmessage": "",

"email": "",

"subspace": ""

},

"06_role": "merchant"

},

"03_item": {

"01_title": "",

"02_description": "",

"03_condition": "",

"04_price": {

"bitcoin": 0

},

"05_shipping": {

"est_delivery": "",

"region": ""

},

"06_images": {

"image_hashes": [

"",

"",

"",

"",

""

],

"image_urls": [

"",

"",

"",

"",

""

]

},

"07_keywords": [

"keyword1",

"keyword2"

]

},

"04_notary": {

"01_guid": "",

"02_pubkeys": {

"pgp": "",

"pubkey": "xxx",

"pubkey_selfsig": "XXX"

},

"03_handle": "",

"04_passcard": ""

}

},

"02_signatures": {

"bitcoin": "",

"pgp": ""

}

},

"02_buyer": {

"02_order": {

"01_id": {

"01_guid": "",

"02_pubkeys": {

"bitcoin": "",

"pgp": ""

},

"03_handle": "",

"04_passcard": "",

"05_contact": {

"bitmessage": "",

"email": "",

"subspace": ""

},

"06_role": "buyer"

},

"02_item": {

"01_semantics": {},

"02_shipping_address": ""

},

"03_multisignature": {

"01_chaincode": "",

"02_multisignature_address": "",

"03_redemption_script": "",

"04_txid": ""

}

},

"02_signatures": {

"bitcoin": "",

"pgp": ""

}

},

"03_merchant": {

"01_shipped": {

"01_shipping": {

"01_tracking_id": "",

"02_shipper": "",

"03_payout": {

"01_payout_address": "",

"02_signed_tx": ""

}

}

},

"02_signatures": {

"bitcoin": "",

"pgp": ""

}

},

"04_buyer": {

"01_delivery": {

"01_item": {

"01_received": true,

"02_dispute": false

},

"02_payout": {

"01_signed_tx": "",

"02_txid": ""

},

"03_rating": {

"01_rate_merchant": "",

"02_rate_item": "",

"03_rate_item_description": "",

"04_rate_shipping": "",

"05_rate_customer_service": "",

"06_feedback": ""

}

},

"02_signatures": {

"bitcoin": "",

"pgp": ""

}

}

}Note: future articles will breakdown the component parts of the contract and how they should be used.

Within the ledger section of the contract, the signing order is divided into several stages. Each stage immediately identifies the party responsible for filling the empty data fields. The user signs the contract and forwards it to the next user in the ledger. The user won't be required to manually send it to the user in the ledger. Rather, the client will verify the signatures first before sending the signed contract to the next party. In a loose sense, this enables OpenBazaar Ricardian contracts to adopt some 'smart' characteristics.

An abstraction of the signing order:

The signing order should be defined in the structure of the JSON contract.

{{Insert something here about notaries}}

Consider a typical exchange between two parties with an arbiter mediating the transaction, where a 2-of-3 multisignature address is generated. The buyer in this exchange sends bitcoins to the multisignature address, to be released upon the pre-agreed conditions with the seller. While seller or arbiter alone cannot steal these funds, there remains a non-zero risk of collusion between them to defraud the buyer. Unfortunately, soley relying upon reputation systems is not an adequate solution this problem, no matter how well designed. An effective strategy is to minimise the risk of collusion by adding more arbiters to the mix, a voting pool. A majority vote by the pool of arbiters makes it more difficult for a corrupted arbiter to defraud the transaction, and is thus a favorable means of managing risk for high value exchanges in OpenBazaar.

Voting pools in OpenBazaar would be created from the list of preferred arbiters from the buyer and seller's profile. In the case of an uneven number of arbiters within the pool, the benefit of the doubt goes to chance with the client randomly selecting a well-ranked arbiter. The total size of voting pool is limited to the maximum number of parties in a multisignature transaction on the Bitcoin network. An important element in forming a voting pool is to prevent the risk of a 'sore loser attack', where the multisignature transaction is constructed without the possiblity of the seller and the arbiters recovering the funds if the buyer fails to initiate the transaction, after receiving a good or losing a bet for example.

Notary pools decrease the overall risk of collusion and increase the redunancy of transactions, a multisignature escrow address is made up of several additional parties on top of the merchant and buyer. For example, an 8-of-15 multisignature escrow address can be created made up of:

- 3 notaries selected by the merchant

- 3 notaries selected by the buyer

- 1 notary selected at random

- 4 keys from the merchant

- 4 keys from the buyer

Signatures from 8 keys are required to release funds from the multisignature escrow address. If the merchant and buyer have any reason to doubt the pool, they can move the keys to a different multisignature address. If there is a dispute, a majority of signatures is required in combination with one of the parties to release funds from the address. No single party can steal the funds, and the likelihood of collusion is reduced with more parties involved.

Notary pools can be designed according to the 'Lucas Algorithim':

Two traders, Alice and Bob, require equal number ("n") of keys, as you do not know a priori who will win the trade (or bet). In general, Alice needs "n" keys, Bob needs "n" keys, and the jury needs "2n - 1" keys. The majority of 2n - 1 is always n. In the simplest case, Alice has one key, Bob has one key, and the jury size (2x1 - 1) is one (i.e., the arbiter decides with Alice or with Bob). In the above example, n = 4. Alice has 4 keys, Bob has 4 keys, and the jury size = (2x4 - 1) = 7. The "best of 7" is of course 4 (= n). The total number of keys is 4n - 1 = 15. The multisig is therefore 8 of 15, which is achieved with Bob + Alice, or Alice + voting pool (majority thereof), or Bob + voting pool (majority thereof). These numbers should work with any integer n > 0.

Interaction of the notary pool with the arbiter is managed over the OpenBazaar application:

The notary pool will received a digitally signed ruling from the arbiter. The ruling can be blinded from the notaries (i.e. encrypted with the public keys of the merchant and buyer), to maintain the privacy of both parties (discussed in more detail below). Aside from the arbitration notes, the ruling will also contain an unsigned bitcoin transaction with:

- Input: the multisignature escrow address

- Output_1: the winning party from arbitration

- Output_2: notary fee

- Output_3: arbiter fee

In more complex settlements, where both parties receive a portion of the funds, additional outputs are added to the transaction. The bitcoin transaction is digitally signed by either both parties, or the winning party with the notary pool and broadcast to the Bitcoin network.

Even with a notary pool, the question remains how users will choose notaries within OpenBazaar? The most direct way is for users to access the storefront of other nodes in the network, select the 'services' tab and manually add them to their list of preferred notaries. Users can also search for nodes on the network that they wish to add on their list. These approach however, assume that the user already knowns what node to trust as a notary.

One approach is for notaries to be accredited by a voluntary private orgaisation, which creates some open standards for notaries to voluntarily subject themselves to in order to earn an 'endorsement badge'. These open standards may include:

- The notary node has an up-time of >22 hours per day

- Communication response times are < 12 hours

- Notaries issue a surety bond held in a multisignature address by the accreditation organisation

This approach is a form of self-regulation, whereby accreditation is earned after demonstrating compliance. The accrediting organisation can also hold the surety bond in the event that an accredited notary defrauds a client. In this scenario, a corrupt notary is excluded from the organisation, their surety bond is forfeit (perhaps used to compensate a defrauded member), and they lose their public accreditation with the association. A notary may choose to become accredited from several such organisations to bootstrap trust.

Technically this can be achieved by the private organisation keep a public record of accredited notaries, digitally signed, that a notary can link to within their 'notary description' field within the client.

From a user's perspective, they can search and filter potential notaries according to the presence or absence of accreditation by various organisations. Of course this does not restrict users from finding and using unaccredited notaries that they prefer.

Data fields within the Ricardian contract can be hashed prior to forwarding to the notary for their digital signature. Nearly all data fields can be hashed with exception to the bitcoin pubkeys necessary to create a multisignature address. Hashing is preferable to encryption with the buyer or seller's public key as the data fields can be easily verified by an arbiter in the event of a dispute, rather than going through additional decryption steps. The goal is to create an immutable record of the product details of the contract while obfuscating them.

For example, imagine that Alice wants to sell an item to Bob that she should not like the notary to be aware of. The unblinded contract that both Alice and Bob see is shown below:

{

"_OpenBazaar_ Contract": {

"OBCv": "0.1",

"Category": "Physical good",

"Sub-category,": "Ask price: negotiable",

"Nonce": "01",

"Expiration": "2014-06-29 12:00:00"

},

"Seller": {

"NymID": "abc123",

"NodeID": "Alice",

"BTCuncompressedpubkey": "044448c02963b8f5ba1b8f7019a03b57c80b993313c37b464866efbf61c37098440bcdcc88bedf7f1e9c201e294cf3c064d39e372692a0568c01565b838e06af0b",

"PGPpublicKey": "xsBNBFQtSk0BB/98EG2qpRRVJUZ0tjwbT88bzjeJl7rhPRWzewvjZDMjjDK0Q9p2q8xm21g1BAgsNV6fqyM8cpnosT6/jYur3h1c+l5YAAWTGw1LYZ44rArMFZ9yq9XuiKH0NEv5xko1+AAKdMnev1ZbU87iRR5YbQXqWCzS2/M+CZ3cY2d/WpJO50zlhofsC1gprtLaBuRmiFaboEjvj/i+a14BvkpmQhhdFlsVSUkUPKUS96hHQfYkY6uJGNC1SCAISaTJAXTMIgIjDRc0/tORAPqi0NrcCfAZJVQuMKBYrqA5acL2cFnehmIYGaCQpexqpV5Lme2jhiFk8/4Fjtl88kqjBUey2tcdABEBAAHNGkJsdWhoYXVhaGEgPGxhbGFAbGFsYS5jb20+wsByBBABCAAmBQJULUpeBgsJCAcDAgkQwltegB4kwqAEFQgCCgMWAgECGwMCHgEAAKvcB/wPLNVWm6iipqKO4hoY45Kxey23uEjVIqHAfNn5J+RkmKnYhEtAn/Q98flh6v7qnTi/GMvP1kbeGdIBob7S6X7z75ZUEIF72Q76qFI7BmuDme2RuKn/xyXRuQuTH0LD/EhPMGQiSjni5kW8ht1g2GpqFQiBKFMmhC4fwSgBQNXLCeDjYK8JvS5RsxLpfcCrvfWJEqjClwjnzXZySjFtZ3qjyry2CLxcPmiprVW7N9D/xJ1KWx3E+dK0zNiqrtxynlv2ZzfgXdu12WGs1YlAt0M1YAcKOSVtUC8iiyRvZYvgFUsuoYNZLDZhRw7PSua4FidYHZnPxMmt2H1ftVqMM9xGzsBNBFQtSl4BB/9wASUgKisYaE0iwp07R1z4Vp0zN/hO77RPV0QPsGcsjmefy1/bl6391pcMAuL7sLvDNXj91bA6SQ50rel2P12YbSvLGgcRpPoxPccQ4myHYOl0tVR4fJcLCyWDmOnz5rGSctZZhAUJ3FaTkeQd3pgzDtdD7M8hZ1GFwMnsw36IUDuyTRo450kNzZV/y9Ai7rjqqjZ86n6h74dp5cUB/w8FVBxAZaFbZYDYPSAsV+ja5CMxasgDhNZwukjRGX3MR/nJNNM+Oy684mi+iAe7ZEcR4m2fDHo/B7oJSTmSfqO21sK9v/K4lRDmJkPYJDpxUMlB/k+ksAgrjehA2h240NFPABEBAAHCwF8EGAEIABMFAlQtSnYJEMJbXoAeJMKgAhsMAADBWAf9Fqj98anrvWlsbtBFwbFu6LF8uNTrtoHNnFfTMOjIR6+ccTIDeMiOOKhEWkZa7VroS3hJXY9Ps0DGjUXQZ5nP0L4IeZOF5+Oj8SPQX+uJfyZ/Ewq/4lpD/DNz9AWyPkDTFLxUfEFJ9kTm1Uue3cV1KKtqeptaFuIL1l7tgaDOi2nxdVq/C937QAiXY6wEUcocaXUOSaWyWjEoiXA7tBRXrp3gxFFs6hl5ECW5gxFymITVm2WlNeHm6Jn9v786bp0Umz8K5+TcPWu08duuOBDw0qAN6g2alt4Cb0IDOOhxmKenIuEHg3RyhCwQwUOpMLlZXxpTWjUzWZOTLEvR9zciXA===28tV"

},

"Physical Good Contract": {

"ItemName": "Little House on the Prairie DVD Anthology",

"Currency": "Bitcoin",

"Price": "0.01",

"Description": [

"The entire collection."

],

"Delivery": {

"Country": "USA",

"Region": "All States",

"EstimatedDelivery": "13 days after triple-signing",

"PostagePrice": "Included in the item price"

}

}

}Bob accesses the contract via the OpenBazaar client for signing. However, as both Alice and Bob want to maintain privacy in their transaction, Bob blinds the transaction first before sending it to the notary.

Contract blinding requires the following steps to take place:

- Bob hashes the original seed contract

- Bob prepares a blinded double-signed contract

- This contract includes the hash of the original seed contract from (1). The purpose of this hash to provide an immutable reference to what Alice and Bob are actually trading.

An example of the blinded contract:

{

"_OpenBazaar_ Contract": {

"OBCv": "0.1",

"Category": "Physical good",

"Sub-category,": "Ask price: negotiable",

"Nonce": "01",

"Expiration": "2014-06-29 12:00:00"

},

"Seller": {

"NymID": "abc123",

"NodeID": "Alice",

"BTCuncompressedpubkey": "044448c02963b8f5ba1b8f7019a03b57c80b993313c37b464866efbf61c37098440bcdcc88bedf7f1e9c201e294cf3c064d39e372692a0568c01565b838e06af0b",

"PGPpublicKey": "xsBNBFQtSk0BB/98EG2qpRRVJUZ0tjwbT88bzjeJl7rhPRWzewvjZDMjjDK0Q9p2q8xm21g1BAgsNV6fqyM8cpnosT6/jYur3h1c+l5YAAWTGw1LYZ44rArMFZ9yq9XuiKH0NEv5xko1+AAKdMnev1ZbU87iRR5YbQXqWCzS2/M+CZ3cY2d/WpJO50zlhofsC1gprtLaBuRmiFaboEjvj/i+a14BvkpmQhhdFlsVSUkUPKUS96hHQfYkY6uJGNC1SCAISaTJAXTMIgIjDRc0/tORAPqi0NrcCfAZJVQuMKBYrqA5acL2cFnehmIYGaCQpexqpV5Lme2jhiFk8/4Fjtl88kqjBUey2tcdABEBAAHNGkJsdWhoYXVhaGEgPGxhbGFAbGFsYS5jb20+wsByBBABCAAmBQJULUpeBgsJCAcDAgkQwltegB4kwqAEFQgCCgMWAgECGwMCHgEAAKvcB/wPLNVWm6iipqKO4hoY45Kxey23uEjVIqHAfNn5J+RkmKnYhEtAn/Q98flh6v7qnTi/GMvP1kbeGdIBob7S6X7z75ZUEIF72Q76qFI7BmuDme2RuKn/xyXRuQuTH0LD/EhPMGQiSjni5kW8ht1g2GpqFQiBKFMmhC4fwSgBQNXLCeDjYK8JvS5RsxLpfcCrvfWJEqjClwjnzXZySjFtZ3qjyry2CLxcPmiprVW7N9D/xJ1KWx3E+dK0zNiqrtxynlv2ZzfgXdu12WGs1YlAt0M1YAcKOSVtUC8iiyRvZYvgFUsuoYNZLDZhRw7PSua4FidYHZnPxMmt2H1ftVqMM9xGzsBNBFQtSl4BB/9wASUgKisYaE0iwp07R1z4Vp0zN/hO77RPV0QPsGcsjmefy1/bl6391pcMAuL7sLvDNXj91bA6SQ50rel2P12YbSvLGgcRpPoxPccQ4myHYOl0tVR4fJcLCyWDmOnz5rGSctZZhAUJ3FaTkeQd3pgzDtdD7M8hZ1GFwMnsw36IUDuyTRo450kNzZV/y9Ai7rjqqjZ86n6h74dp5cUB/w8FVBxAZaFbZYDYPSAsV+ja5CMxasgDhNZwukjRGX3MR/nJNNM+Oy684mi+iAe7ZEcR4m2fDHo/B7oJSTmSfqO21sK9v/K4lRDmJkPYJDpxUMlB/k+ksAgrjehA2h240NFPABEBAAHCwF8EGAEIABMFAlQtSnYJEMJbXoAeJMKgAhsMAADBWAf9Fqj98anrvWlsbtBFwbFu6LF8uNTrtoHNnFfTMOjIR6+ccTIDeMiOOKhEWkZa7VroS3hJXY9Ps0DGjUXQZ5nP0L4IeZOF5+Oj8SPQX+uJfyZ/Ewq/4lpD/DNz9AWyPkDTFLxUfEFJ9kTm1Uue3cV1KKtqeptaFuIL1l7tgaDOi2nxdVq/C937QAiXY6wEUcocaXUOSaWyWjEoiXA7tBRXrp3gxFFs6hl5ECW5gxFymITVm2WlNeHm6Jn9v786bp0Umz8K5+TcPWu08duuOBDw0qAN6g2alt4Cb0IDOOhxmKenIuEHg3RyhCwQwUOpMLlZXxpTWjUzWZOTLEvR9zciXA===28tV"

},

"Buyer": {

"NymID": "def456",

"NodeID": "Bob",

"BTCuncompressedpubkey": "04a34b99f22c790c4e36b2b3c2c35a36db06226e41c692fc82b8b56ac1c540c5bd5b8dec5235a0fa8722476c7709c02559e3aa73aa03918ba2d492eea75abea235",

"PGPpublicKey": "xsBNBFQum5sBCACGWTFtJElTxRGG7OnHDfaEnPE5fUx57a5i5q5L7Bk6mG3h6omPO7MhhFFtKjbszdq1WUSogvTF7JTqzblC843i6D0XZOCfNEvj2jbMXu7N6QkX4otEOleVZdiRrSkBK8ubdGcaSXsKEONs37nRAfSCOdVz1JZvCtV7fT/oiaqR47osu2OMYOExpAASwF6f1CfglC6uWLnG34e3use+ILrev2WKREINLU4Z5cuZET59gotfqpfH2l3Wo22SBn+HWJl8yIsK3/QB/7oRtPN4wSTky0jJE7+bzE4/F2qjoXPUiqWMDfdF+ALbFs+GBsv8Gtfsmuawr3ZzzPi3fElAoXirABEBAAHNIE9CVGVzdDIgPG9idGVzdDJAb3BlbmJhemFhci5vcmc+wsByBBABCAAmBQJULpuqBgsJCAcDAgkQKr7omyUpIU8EFQgCCgMWAgECGwMCHgEAACP9B/0cjB3CrF4wARoPblCdWijTKq6MwxG/iUp7zOXiIoxF4cXDzTjtkcVBaDOj5Y5wlL7UQc4zJy4c3NUh7qrOzYxNVfqfF9xTVmOtECTYa+hFP4HAxl1v1KAhrhiHren9jOkAc+LRyyMMmM59JcpjY37VsynzdJrLTz3W6fa4PAdSy9b1Ezmg7svgOzPSz/xwWooQBk/2pKH6AF0+wrCMKbztutnf6KMlZoxkbrMcAYQkiCMaRrvNdGcJevgpsViqQ06f9eKuZrmHAhvpuAkT1Xh/YyYZ26RdPKFmpk5KPEPSQbzl8GcS75TfgNiZCBM+WoT1h7F82Tgo30MHxh/dqewFzsBNBFQum6wBCACEEU6kx2ZhYEI+uSExGlby11hPz4QDLrsNWVH4sHJS6Ln05lt30Le55MEpTNiRXAZa/Q70Dt5konpPiQ9+Y6L7WNL3pTlVnDm0Wl6g2Obf1Brg1xqmFAW44u1p2kr8yc/kNh87L2+y3p5qHd0hFV++ex7Fg5oSeow2lQ1lNwMbCFOgml1ddY9Ls+ZsRCBEbBsWD/gfd4wgBtLZBzokx2QueBh/sZrINtLLqXht8C05MpvTQS1m9G4J+sek12c1R6I/O2lcg9sbntKrclMBX1ZcSWh/dkWtG/fgKqYrLxHF9noPiHFTYUlq+5I0KDJUHle6CLb5dsWUrIBHwqI3rLQzABEBAAHCwF8EGAEIABMFAlQum8YJECq+6JslKSFPAhsMAADNYgf+MeBZIlXWbG1p99LNGJWwOyznqinhvj2FWTJAeBpWz+MT35enq+RG7jTziGW3UdvkojLFgMFFZFU34QXKRBOBwXVwXebOAdFyeO0thB7J7mt2esteJGNy5pEegWma97618ZUCOsBmKhfNGGxOfT0+x5qHLpb4X54neA7LxaF3jSBQTut/TTOZNVWscwM+w4hLLzB5Q/0RC6nmQQ03nCCqScQK8WfRohx/vRnXIDmHRsm4p8FJwGBZbT5clOVkon8Bj0Gkp83y9TfJX0CpGrwmbnuaWXPU4EI6+G14XHu3p9xwo3L2Bc8jli0+GVZ7SJCCRdJ+/66NvJYHIVzzbxlvkQ===7H5F"

},

"Physical Good Contract": {

"Blind_contractHash": "544e7ddb8b5b7771303a9d45449b8de328d331b1c7cc473840017f1d67a35542",

"Currency": "Bitcoin",

"Price": "0.01"

}

}As per the standard process, the buyer forwards the contract to the notary who adds a third digital signature to the contract. However, the notary will not be able to determine the contents of the good being sold on OB. OpenBazaar client, exports and emails it as an attached .json file directly to Bob. Bob can then who imports it into the OpenBazaar client. Bob signs the contract and selects a notary.

The client/app enables the user to fulfill any desired role on the network (merchant, buyer, notary, arbiter). The UI/UX will likely vary on the type of trade to be conducted.

In this article we attempt to design a decentralised rating and review system for the sale of physical goods on the OpenBazaar network. Ratings and reviews are sometimes considered interchangeable with the challenge to create a global decentralised reputation system. For OpenBazaar, this is not the case as the system described here is:

- Performance based

- Made on a per item basis

- Not applicable to other types of marketplaces built on the OpenBazaar platform

Decentralised reputation refers to the overall trustworthiness of an identity within a network. In the future, decentralised reputation can be layered over OpenBazaar if and when it is ever developed. For ratings and reviews, they are strictly concerned with the merchant performance of that identity on the network. Both systems are theoretically compatible and need to be fully developed.

Ratings and reviews are defined in this article as:

- Ratings - scores on the behavior of the merchant, the quality of the item, and shipping time.

- Reviews - written summary of the trade experience with the merchant

As mentioned earlier, ratings and reviews are made on a per trade basis.

Who are we rating?

The merchant.

Who is making the rating?

The buyer.

Why isn't there a rating of the buyer by the merchant?

There is very little for the buyer to get wrong in a trade other than failing to release funds from the escrow address, whereby the notary would have to step in to payout the merchant. As a result, a notary can develop internal systems to prevent or mitigate in advance this type of behavior. Also buyer reviews are not common in typical e-commerce platforms for physical goods.

Side note: For trades using mutually-assured destruction escrow addresses (i.e. 'MAD' 2-of-2 multisig), decentralised reputation is a critical metric for users to predict the likelihood of good behavior by the counterparty identity.

- Sybil attacks - fake ratings made by an attacker using sockpuppets identities

- Distributed storage - ratings must be persistent publicly accessible and immutable

Sybil Attacks

- Sybil attacks can generally be mitigated by increasing the cost in resources or time to perform an action

- In OpenBazaar, this can be achieved in a couple of ways:

- Demonstrating a proof of trade

- Showing evidence of a trade by a triple-signed Ricardian contract (i.e. signed by merchant, buyer, and notary)

- But this approach is not good for the privacy of the buyer

- Notary validation

- The notary validates that an anonymous rating and review comes from a valid trade with the merchant

- Preserves the privacy of the buyer, provided the merchant or notary doesn't reveal this information

- Assumes that the notary is reputable to begin with

- Either approach does not fully eliminate the possibility of a Sybil attack

- Rather it will significantly increase the cost to perform such an attack perhaps to the point where they are discouraged

Distributed Storage

- Ratings need to be stored somewhere that can be accessed by anyone at any time

- As a result, these ratings cannot be hosted by the buyer or merchant themselves, which may omit negative ratings on top of having a transient presence on the network

- Notaries may host ratings as a service

- If a prominent notary is taken offline, then the rating and review data may be lost forever

- Notary is hosting is encouraged, but decentralised and distributed redundancy should still be found

- Options for persistent distributed storage:

- Bitcoin blockchain

- Blockstore

- ChainDB

- Namecoin or other blockchains

- Subspace

- Of the above options, the first three leverage the Bitcoin blockchain in different ways

- All except the first option require other users to maintain a parallel network to Bitcoin, where the incentive to do so may or may not be clearly defined

- Specific application and criticisms:

- Bitcoin blockchain

- Blockchain bloat

- Limit to how much you can store in

OP_RETURN

- OpenBazaar or Blockstore DHT

- The rating/review data can be embedded into

OP_RETURNin the blockchain, which can then be used as a reference in the OpenBazaar or Blockstore DHT for the full rating and review data - In the case of OpenBazaar, data embedded into the DHT can be made to confirm a certain specification to restrict space and counter some Sybil attack vectors

- The incentive structure for running a node on the Blockstore DHT is unclear for now

- Also unclear how robust and persistent data storage will be on either DHT, or how some Sybil-spam attacks will be mitigated

- ChainDB

- Parallel network must be run alongside OpenBazaar to push ratings into the database

- In effect creating a crypto-asset just to make a rating: overkill

- Project is still a theory for now, nothing implemented or tested

- Namecoin (or another blockchain)

- Rating data is not really permanently hosted, as data storage needs to be renewed periodically

- As a result, reputations can disappear if not properly maintained

- Reputation cannot have a statute of limitations!

- Limit to how much data you can store onto Namecoin

- Subspace

- Storage must be paid for on the Subspace network over time

- Parallel network to Bitcoin and OpenBazaar

There is no magic bullet, any choice is associated with different trade-offs.

In our view, storing merchant ratings is best achieved by directly embedding the rating into the blockchain.

- The rating score is embedded into the blockchain via

OP_RETURNas an extra output of the payout transaction from the multisignature escrow address- This is the transaction that either release funds from multisig to the merchant (in a successful trade), or to the buyer as a refund (in an unsuccessful trade)

- The rating score follows a standardised format with the following components:

- OpenBazaar rating tag

- Concise tag to identify a transaction containing an OpenBazaar rating

- Merchant rating score - [-1,0,1] overall rating of the merchant

- -1: Negative rating

- 0: Neutral rating

- 1: Positive rating

- Item rating score - [1-5; lowest-highest rating] for each category

- Item description: Was the item delivered in the condition and quality described in the contract?

- Delivery time: Was the item delivered within the time specified in the contract?

- Customer experience: What was the interaction with the merchant like?

- Global unique identifier (GUID) of the merchant being rated

- Item unique identifier (IUID) of the item being sold

- Similar to short ID

In plain text, the rating score would look like this:

OBR 1 5 5 5 b20c6947b11ac5bdb4b4338bc196df0b0f3f452d 23TplPdS

(tag, merchant rating, item rating (description, delivery time, customer experience, merchant GUID, IUID)

As a hex value, it looks like this:

4f4252202b31203520352035206232306336393437623131616335626462346234333338626331393664663062306633663435326420323354706c506453

The overall size of the rating score should be around 62 bytes, well under the new 80 byte limit for OP_RETURN.

How do we determine whether a reputation score is valid, as anyone can create 100 transactions to give themselves a positive rating?

- The notary is in the best position to validate whether a rating is from a valid OpenBazaar transaction

- The buyer can add an extra output to the payout transaction sending a microtransaction to the notary

- The address can be called the 'rating validation address'

- The client can validate that the address is associated with the notary on the OpenBazaar network

- The notary can host an open record of valid OpenBazaar transactions using

OP_RETURNandTXIDas the references (tied into Reviews, described below)- Bitcoin transactions that have tagged the notary erroneously can be ignored

- These only enrich the notary as a transaction needs to be made to their address

Where and how are reviews stored decentrally?

OP_RETURNis not large enough to store reviews, unless they are restricted to being < ~75 characters (which isn't very practical)- A transaction with multiple

OP_RETURNoutputs are not standard, so you'd have to store the rating and review within a singleOP_RETURNoutput - Either the OpenBazaar or Blockstore DHT appears to be the best solution to store item reviews

OP_RETURNhex containing the rating (described above) will be used as the reference hash

- A full outline of the Blockstore protocol can be found here.

- A similar model would be taken to store reviews within the OpenBazaar DHT with the following features:

- Restrictions on the maximum size of the written review

- Easier to embed within the process of executing a transaction on the network

- Leverages financial motivation of users on the network to indirectly incentivise nodes storing rating/review data in the DHT

Irrespective of the DHT, the data structure for OpenBazaar rating and review may appear this way:

{

"_OpenBazaar__opreturn_ref": "4f4252202b31203520352035206232306336393437623131616335626462346234333338626331393664663062306633663435326420323354706c506453",

"trade_ref":{

"merchant_guid": "b20c6947b11ac5bdb4b4338bc196df0b0f3f452d",

"notary_guid": "f4b5c505fd5abe9d9c631be65dfa52c9df34ae3c",

"contract_hash": "3dbb901141c71351bcafee94274a9c67f0b3e9065531fbc7c6f9d0abd70c641a",

"item_code": "23TplPdS"

},

"ratings": {

"merchant_rating": 1,

"item_description": 5,

"delivery_time": 5,

"customer_exp": 5

},

"review": "That bucket of nuts was amazing. Loved the free funnel!"

}- As mentioned earlier, it is important that the

Buyerdetails are omitted from this rating to preserve their privacy as much as possible.

- Sybil rating attack

- A user creates multiple nodes to cover multiple merchant, buyer, and notaries to issue fake positive or negative ratings

- An underlying assumption is that a few notaries will have a large market share, thus positive/negative ratings from an obscure notary may not be taken seriously

- Blockchain bloat

- The use of

OP_RETURNwill contribute to blockchain bloat, resulting in nodes automatically pruning this data from the blockchain- May result in the increased trend towards centralisation

- However,

OP_RETURNis such a valuable utility, we consider it unlikely that this data storage entry will be closed. - We already have a small centralisation risk by using Obelisk servers as block explorers.

Dionysis Zindros, National Technical University of Athens [email protected]

pseudonymous anonymous web-of-trust identity trust bitcoin namecoin proof-of-burn timelock decentralized anonymous marketplace _OpenBazaar_

Webs-of-trust historically have provided a setting for ensuring correct identity association with asymmetric cryptographic keys. Traditional webs-of-trust are not applicable to networks where anonymity is a desired benefit. We propose a pseudonymous web-of-trust where agents vote for the trust of others. By disclosing only partial topological information, anonymity is maintained. An inductive multiplicative property allows propagation of trust through the network without full disclosure. We introduce additional global trust measures through proof-of-burn and proof-of-timelock to thwart Sybil attacks through an artificial cost of identity creation and maintenance and to bootstrap the network. Existing blockchains are used to provide friendly names to identities, and the network is applied to a commercial setting to manage risk. Finally, we highlight certain attacks that can compromise the trust of the network under certain assumptions.

Webs-of-trust are traditionally a means to verify ownership of encryption and signing keys by a particular individual whose real-world identity is known. The first widely deployed web-of-trust is the GPG/PGP web-of-trust [Zimmermann][Feisthammel]. In these webs-of-trust, a digital signature on a public key is employed to indicate a binding between a digital cryptographic key and an identity. Such a digital signature does not designate trust, but only signifies that a particular real-world individual is the owner of a digital key.

Webs-of-trust have also been utilized for different purposes in various experimental settings. In Freenet [Clarke], it is used to guard against spam [Freenet WoT]. In a commercial setting, the Bitcoin OTC web-of-trust successfully attempts a centralized approach to establish a true trust network [OTC], contrasting identity-only verification webs-of-trust of the past.

The aim of our web-of-trust is to construct a means to measure trustworthiness between individuals in a commercial setting where goods can be exchanged between agents. The goal of such a measure is to limit, as much as possible, the risk of traders in an online decentralized anonymous marketplace. We are proposing a system to be used in production code as a module of OpenBazaar [OpenBazaar], a peer-to-peer decentralized anonymous marketplace that uses bitcoin [Nakamoto] to enable transactions.

Risk management in OpenBazaar is based on two pillars: On one hand, Ricardian contracts are used to limit risk through mediators, surety bonds, and other means which can be encoded in contract format [Washington]. On the other hand, the identity system is used to establish trust towards individuals. In this paper, we introduce the latter and explore its underpinnings.

Trust management in OpenBazaar is established through two different types of mutually supporting systems; projected trust and global trust. Projected trust is trust towards a particular individual which may be different for each user of the network; hence, trust is "projected" from a viewer onto a target. Global trust is trust towards a particular individual which is seen as the same from all members of the network. Projected trust is established through a pseudonymous partial knowledge web-of-trust, while global trust is established through proof-of-burn and proof-of-timelock mechanisms.

The identity system is threat modelled against various adversaries. We are particularly concerned about the malicious agents highlighted in this paragraph, with their respective abilities.

First, we wish to guard against malicious agents within the network. If there are malicious buyers, sellers, or mediators, the goal is to disallow them from gaming the network and obtaining undeserved trust.

Second, we wish to guard against malicious developers of the software. If a developer tries to create a bad patch or influence the network, this should be detectable, and the honest agents should be able to thwart against such an attack by choosing not to upgrade by inspecting the code. The system must not rely on the good faith of developers; it is open source and decentralized.

Third, we wish to guard against governments and powerful corporations that wish to game or shut down the network. These agents are not always modelled as rational, as their objectives may involve spending considerable amounts of money and processing power to game the system, with no obvious benefit within the system bounds. Their benefits may be legal, economical, or political, but cannot be simply modelled. Their power may be legal and can defeat possible single points-of-failure on the network.

However, we assume that the malicious agents have limited power in the following areas. We assume that the bitcoin, namecoin, and tor networks are secure. We assume that malicious agents have limited processing power, bandwidth, monetary power and connectivity compared to the rest of the network. As long as malicious agents control a small portion of such power, the network must remain relatively secure.

The limited connectivity assumption requires additional explanation. We assume that a malicious agent will not be able to find and control a graph separator for any non-trivial induced graph between any two parties on the web-of-trust. This assumption is detailed in the sections below.

Our trust metrics are heuristic; some trust deviation for malicious agents who try to game the system with a lot of power is acceptable. However, it is imperative that trust remains "more or less" unaffected by local decisions of agents, unless these decisions truly indicate trustworthiness or untrustworthiness. Trust should be primarily affected by trading behavior, and not by technical influence on the network.

The OpenBazaar web-of-trust maintains three important factors: First, it maintains strict pseudonymity through anonymizing mechanisms; second, it establishes true trust instead of identity verification; and third, it is completely decentralized.

The OpenBazaar web-of-trust is used in a commercial setting. Trust is used to leverage commercial risk, which involves losing money. Traditional identity-verifying webs-of-trust such as GPG are in purpose agnostic about the trustworthiness of the web-of-trust participants. That type of web-of-trust verifies the identity of its members with varying certainty. However, it remains to the individual to associate trust with a particular person for a particular purpose: Whether they can be trusted with money, for example [GPG identity].

In OpenBazaar, the participants are inherently pseudonymous. In this setting, we wish to maintain an identity for each node. This identity is strictly distinct from the operator's real-world identity. While the operator may choose to disclose the association of their real-world identity with their pseudonymous node identity, the network gives certain assurances that such pseudonymity will not be broken. Hence, pseudonymity is closely related to anonymity: Pseudonymity allows the creation and maintenance of an online "persona" identity with a certain history; anonymity ensures the real-world identity of the persona operator remains unassociated with the persona. Hence, our goal is to provide both pseudonymity and anonymity.

A true web-of-trust is a directed graph where nodes are individuals and edges signify trust relationships. In contrast to identity-verifying webs-of-trust, in a true web-of-trust, edges do not signify identity verification; they signify that the edge target can be trusted in a commercial setting. For example, when trust is given to a vendor, it signifies that the vendor is trustworthy and will not scam buyers by not delivering goods. When given to a mediator, it signifies that the mediator is trustworthy will resolve conflicts between transacting parties with a neutral point of view judgment. And when given to a buyer, it signifies that the buyer is trustworthy and will pay the money she owes. Clearly, trust is not symmetric.

While identity verification is a concept successfully leveraged by individuals for secure communications and other transactions, it is meaningless to try to verify the identity of a pseudonymous entity, because a pseudonymous entity is the cryptographic key in and of itself, and therefore identity verification would constitute a tautology. It is therefore required to adopt a different meaning of "trust" than in a traditional setting of real-world identities. Hence, trust in this case signifies the trustworthiness of an individual in a commercial setting, their financial dependability, their reliability as mediators, and their credibility as trust issuers [1] [2].

Each node in OpenBazaar is identified by its GUID, which uniquely corresponds to an asymmetric ECDSA key pair. This GUID is the cryptographically secure hash of the public key. The anonymity goal is to ensure this GUID remains unassociated for any real-world identity-revealing information such as IP addresses.

Each GUID is associated with a user-friendly name. These user-friendly names can be used as mnemonic names: If someone loses their trust network by reinstalling the node without first exporting, they know that certain agents remain trustworthy. Furthermore, user-friendly names are used in the trust bootstrapping procedure in which it becomes easier to peer-review that the bootstrapped nodes are the correct ones. Finally, user-friendly names can be exchanged between users out of the software usage scope; for example, a user can directly recommend a vendor by their user-friendly name to one of their friends via e-mail.

To maintain a cryptographically secure association between node GUIDs and user-friendly names, we utilize the Namecoin [Gilson] blockchain. A node can opt-in for a user-friendly name if they so choose. To create a user-friendly name for their GUID, they must register in the "id/" namecoin namespace [Namecoin ID] with their user-friendly name. For example, if one wishes to use the name "dionyziz", they must register the "id/dionyziz" name on Namecoin. The value of this registration is a JSON dictionary containing the key "OpenBazaar" which has the GUID as its value. As Namecoin ids are used for multiple purposes, this JSON may contain additional keys for other services. The namecoin blockchain ensures unforgeable cryptographic ownership of the identity. When a node broadcasts its information over the OpenBazaar network, they include their user-friendly name if it exists. If a node claims a user-friendly name, each client verifies its ownership by performing a lookup on the namecoin blockchain. If the lookup succeeds, the name is displayed on the OpenBazaar GUI and the information is relayed; otherwise the information is discarded.

As namecoin names can be transferred, this allows for participants to transfer their identity to other parties if they so desire; for example, a vendor can transfer the ownership of their store by selling it.

The most obvious and naive choice for a trust system in a commercial setting is a global voting system. While this solution is obviously flawed, it constitutes an important foundation upon which the next ideas are built. In this section we describe this idea in order to determine its flaws, which are solved in our next proposal.

In typical centralized systems, including eBay and Bitcoin OTC, there is a global rating which is determined as the sum of the individual ratings of others towards an individual. Attacks of fake ratings are taken care in the system in an ad hoc fashion which is enabled by the centralized nature of the system.

In decentralized systems, Sybil attacks [Douceur] make this situation particularly more challenging and without an easy way to resolve. Hence, this naive solution is undesirable. The solution to this problem is to first introduce a cost of identity creation and maintenance for global trust, and allow for the trust through edges to be projected. We explore these solutions below.

It is a conclusive result in the literature that, by analyzing graph relationships between several nodes, given certain associations between nodes and real identities, it becomes possible to deduce the real identities behind other nodes. In particular, if an attacker is given only global topological information about a web-of-trust as well as some pseudonymous identity associations with real-world identities, they can deduce the real-world identities of other nodes [Narayanan]. Hence, by revealing the complete topology of the web-of-trust graph between pseudonymous identities, an important loss of anonymity arises. For this reason, we propose a web-of-trust with partial topological knowledge for each node. Under this notion, every node only has knowledge of its direct graph neighbourhood – they are aware of the direct trust edges that begin from them and end in any target. This does not disclose any information about the total graph, as they are arbitrarily selected by each node. These ideas have been explored previously in the literature as friend-to-friend networks [Popescu].

In the pseudonymous [3] web-of-trust, each node indicates their trust towards other nodes that they understand are trustworthy. This understanding can come from real-life associations among friends who know the real identity of the pseudonymous entity. An indication of trust does not harm anonymity in this context. This understanding can also come from external recommendations about vendors using friendly names. For instance, under a threat model that trusts some centralized third parties, it is possible to establish trust in this manner. As an example, if a vendor is popular on eBay, and a buyer trusts eBay, the vendor can disclose their OpenBazaar user-friendly name on their eBay profile, and the buyer may opt to trust that identity directly.

Trust is indicated as edges with a source, a target, and a weight. The weight is a floating-point number from -1 to 1, inclusive, with 0 indicating a neutral opinion, -1 indicating complete distrust, and 1 indicating complete trust. These can be displayed in a graphical user interface in a more simplistic manner; for example, the canonical client may opt to present a star-based interface for positive trust, and flagging for negative trust; or, alternatively, it may choose to present a simple thumbs-up and thumbs-down option, indicating discrete trust of 1 or -1 if employed, or 0 if not used [4]. These trust edges remain local and are not disclosed to third parties. We call the direct edges "direct trust" and the weights will be denoted as w(A, B) to indicate the direct trust from node A to node B.

As topological knowledge is partial, we resolve the projected trust between nodes through induction. Let t(A, B) denote the projected trust as seen by node A towards node B. Projected trust is then defined as follows:

t(A, B) = w(A, B), if w(A, B) is defined

t(A, B) = a Σ w(A, C) t(C, B) / |N(A)|, for C in N(A), if w(A, B) is undefined and w(A, C) > 0

Where:

t(A, B)denotes the projected trust from A to B.w(A, B)denotes the direct trust from A to B.N(A)denotes the neighbourhood of A; the set of nodes to which A has direct trust edges.|N(A)|denotes the size of the neighbourhood of A.αis an attenuation factor which is constant throughout the network.

The meaning of the above equation is very simple: If Alice trusts Bob directly, then Alice's trust towards Bob is clear. If Alice does not trust Bob directly, then, since we wish to retain only partial topological knowledge, Alice can deduce how much to indirectly trust Bob from her friends. She asks her friends how much they trust Bob, directly or indirectly; the trust from each friend is then added together to produce the projected trust. However, the trust contributed by each friend is weighted based on the local direct trust towards them; if Alice trusts Charlie directly and Charlie trusts Bob (directly or indirectly) then the projected trust that Alice sees towards Bob is weighted based on her trust towards Charlie; for example, if Alice trusts Charlie a little, he's not allowed to vouch for Bob a lot. Finally, the projected trust is normalized based on the number of friends one has, so that it remains within the range from -1 to 1.

The condition w(A, C) > 0 is imposed so that negatively trusted neighbours are unable to vouch for their trust towards others – otherwise they would be able to lie about their trust towards others if they knew they were negatively trusted and impose onto them the opposite trust from what they claim.

The attenuation factor α is used to attenuate trust as it propagates through the network. Thereby, nodes further away from the source gain less trust if more hops are traversed. We recommend a network-wide parameter of α = 0.4 as is used by Freenet, but this can be tweaked based on the network's needs.

This simple[5] algorithm assumes that trust is transitive; if Alice trusts Charlie and Charlie trusts Bob, then Alice trusts Bob[7]. This is a strong assumption and may not always hold in the real world. Nevertheless, we believe it constitutes a strong heuristic that allows a network to deduce trust with partial topological knowledge.

It seems worthy to compare this approach to existing webs-of-trust to point out their differences. In contrast to GPG [GPG identity], our proposal maintains both anonymity and true trust. In contrast to Freenet, trust is used for commercial purposes and not just to fight spam. In contrast to Bitcoin OTC, the network is decentralized, the topology is only partially known, and the trust is only projected and not global.

Certain services provide webs-of-trust in a centralized way, but they do not advertise them as such. eBay ratings provide webs-of-trust, but the topology is globally known and the platform is centralized. Facebook's social graph provides trust through friendships. Interestingly, Facebook's social graph allows partial topological knowledge depending on the privacy settings of the participants. However, centralization is still a problem. In centralized solutions, pseudonymous identities through user-friendly names can also be maintained without a blockchain. The simplicity of implementation benefit is also a strong one.

Centralized solutions have the drawback of a single-point-of-failure. As one of the goals of OpenBazaar is to avoid Achilles' heels (single points of failure), centralized solutions become unacceptable. The purpose is, for instance, to eliminate the ability for government intervention in the web-of-trust through secret warrants served to the administrators of such a centralized system that may require the handover of private encryption and signing keys.

This framework is susceptible to a man-in-the-middle attack which is unavoidable in pseudonymous settings. The attack works as follows: A malicious agent wishes to gain trust as a vendor without really being a trustworthy vendor. They first create an OpenBazaar vendor identity. Next, they choose one other vendor that they want to impersonate. They subsequently replicate their product listing as their own. They also monitor the actual vendor's catalog for product changes, and they relay messages between buyers and the actual vendor when buyers message them. When a buyer purchases a product for them, the rogue vendor also forwards the purchase to the real vendor. Notice that this problem does not directly apply to mediators.

If, after the purchase, the buyer and seller rate each other positively, this rating will not impact the actual parties, but will only be reflected on the rogue vendor. Hence, the rogue vendor will gain trust as both a seller and a buyer without actually being either. This process can be automated. At a later time, the rogue vendor can use the man-in-the-middle position to read encrypted messages between buyers and sellers and may sacrifice their maliciously gained reputation to cheat on a desired buyer or seller. Continuous operation of such rogue nodes can undermine the network.

It is difficult to guard against such attacks. The question of whether someone "really" knows a pseudonymous vendor becomes philosophical; what does it mean to know someone who is pseudonymous to you? And if a man-in-the-middle vendor is always delivering goods, are they not also a trustworthy agent? It is recommended that users establish direct trust only with pseudonymous vendors whose real identity they already know, or have signals that the pseudonymous vendor is not being man-in-the-middled. The latter is difficult to establish, but may be possible through independent verification on different networks and a continued trustworthy history. If we assume that the delivery of products will not be intercepted, the product delivery itself may be used as a mechanism to include a physical copy of key fingerprints in order to establish that no man-in-the-middle is being present.

Nevertheless, negative trust is semantically a different notion from positive trust. Negative trust can be attached to vendors whose identity is unknown; if a man-in-the-middle behaves in an untrustworthy manner, it is imperative to rate them negatively. This distinction between positive and negative trust is made clear in the condition for w(A, C) > 0 to be positive in the equations above. It is a challenging problem to communicate this difference to the user via a clear user interface.

Feedback can be given by buyers to vendors, by vendors to buyers, and by buyers and vendors to mediators in text form. Feedback is a piece of text from a particular source pertaining to a particular target. Keeping the above man-in-the-middle vendor attack in mind, it may in cases not make sense to rate vendors or buyers directly if their real identity is unknown by the rater, even if they trade fairly, unless they can establish an existing trust relationship towards them in order to at least determine their legitimacy.

To avoid fake feedback, feedback must only be relayed by the OpenBazaar client if it is from a node that has transacted with the target. Therefore, feedback must be digitally signed and include a reference to the transaction that took place – the hash of the final Ricardian contract in question, as well as the bitcoin transaction where it was realized.

However, given that transactions are free to execute, to avoid Sybil attacks from vendors or buyers who transact with themselves, feedback must only be trusted when it is given from parties that are already trusted using the total trust metric defined below. Otherwise, it must not be displayed or relayed.

It is hard to establish trust targeting a new node on the network with no web-of-trust connections to it. This issue is addressed in the Global Trust section. However, it is easier to allow new users entering the network to trust individuals who have established some trust through the web-of-trust. Bootstrapping trust is widespread practice in the literature [Clarke].

This bootstrap can be achieved by including a hard-coded set of OpenBazaar node key fingerprints that are known to be good in the distribution. At the beginning, these can be the OpenBazaar developers. It is crucial that the number of nodes included is wide so that no individual can influence the bootstrapped trust. Advanced users are advised to further diminish the weights of the direct edges to the bootstrap-trusted nodes and to include higher-weighted edges to people they physically trust.

The special bootstrapping nodes must be configured to always respond to trust queries, regardless of whether they trust the query initiator.

This practice in particularly useful to guard against illicit uses of the network, which have been experienced in similar, centralized but anonymous solutions [Barratt]. By ensuring the bootstrap-trusted nodes highly rate only non-illicit traders, it is expected that the network will promote legitimate uses of trade. While black market goods can still be traded, the user will be required to opt-in for such behavior by manually introducing trust to nodes who highly rate trusted black market vendors.

The web-of-trust security strongly depends on the size of graph separators. Let us examine the trust as seen from a node A to a node B. Let G' be the graph induced from the web-of-trust graph G as follows: Take all the acyclic paths from A to B in G whose every non-final edge is positive. These contain nodes and edges. Remove all nodes and edges that are not included in any such path to construct graph G'. Then G' is the induced trust graph from A to B. An (A, B) separator is a set of nodes of G' which, if removed from the graph, make the nodes A and B disconnected.

We define an entity "controlling" a set of graph nodes as being able to arbitrarily manipulate the reported t and w functions when the controlled nodes are inquired about their trust beliefs.

We will prove the following theorem for any separator. The smallest separator, mentioned below, is simply easier to manipulate by a malicious party, as they are required to control a smaller set of nodes.

Theorem: A malicious entity controlling the smallest (A, B) separator on the induced graph G' will be able to change a negative projected trust to a positive projected trust towards the target as seen on the original graph G.

Proof: Let S be any (A, B) separator on G'.

Since the trust from A to B was originally negative, this means that A and B are connected on the induced graph G'. As the projected trust is negative, this means that there are direct negative edges in G' from some intermediate parties B1, B2, ..., Bn to B; these edges cannot be indirect, as indirect edges are not traversed for trust discovery.

We will show that the trust through any of Bi can be manipulated to be positive. Indeed, take some arbitrary Bi. Then there will exist some paths from A to B with Ci as their penultimate node. Take some arbitrary path P_i,j from A to B through Bi. We will show that this path can be manipulated to produce positive trust. Since S separates A and B, then there must exist some element s in S that is also in P_i,j. Since s is controlled by the malicious entity, they can modify their claimed direct trust towards B and set it to 1. They can also completely ignore any indirect trust, including Bi's opinion:

w(s, B) = 1

Through this mechanism, every path can be manipulated through the control of S. Therefore, all paths ending in a negative edge can be eliminated. Since A and

B were originally connected, they will remain connected through this trust manipulation. Finally, at least one path ending in a positive edge will exist.

Therefore, since t(A, B) will be a sum of positive terms, A's projected trust towards B will be bounded from below as follows:

t(A, B) >= α t(A, s) / |N(s)|

But t(A, s) must be necessarily positive. Therefore, t(A, B) must also be positive on the induced graph. However, projected trust on G is only based on results on the (A, B) induced graph G', and the value of t(A, B) will necessarily be the same as seen on G. QED.

We have shown that a determined attacker can manipulate trust if they control some separator on the network. Therefore, it is crucial to avoid hub nodes in the network, and especially the existence of trust through only non-disjoint paths. As the web-of-trust develops, it is important to form trust relationships that connect nodes from regions with long distance.

This result is expected; a separator of size 1 is essentially an Achilles' heel for the system. Such single-points-of-failure necessarily centralize the web-of-trust architecture and completely undermine the decentralized design.

As one of the web-of-trust goals is to disallow malicious agents to learn the global network topology, it is crucial that the default node configuration is to not respond to trust queries initiated by nodes they do not trust. If this mechanism is not employed, a malicious entity can query all known network nodes and eventually deduce the global network topology easily.

The exception to this is bootstrapping nodes, which, due to necessity, must be configured to answer all trust queries. Some ε-positive trust can be used as the minimum threshold of trust below which the canonical client does not respond to queries. To ensure queries are authenticated, imagine a query from A to C about whether B is trustworthy. The query must be signed with A's OpenBazaar private key to ensure topological information is not revealed to unauthorized parties asking for it. The query must be encrypted with C's OpenBazaar public key to ensure that nobody else can read it, even if the inquirer is authorised. Finally, the response must be signed with C's private key, to ensure that trust is not manipulated as it travels the network, and encrypted with A's public key, again to ensure topological confidentiality.

In this sense, most trust must necessarily be mutual. However, the topology of the graph still remains directed, as the trust weights can be different in either direction.

It is worthy to attempt an association of the web-of-trust network with other identity management systems. However, given the highlighted differences in the previous section, such an association would compromise some of the security assumptions of the model. It is therefore mandatory that interconnection with other networks is an opt-in option for users who wish to forfeit some of our security goals.

An interconnection with the GPG web-of-trust may be achieved by allowing OpenBazaar nodes to be associated with GPG keys. A particular OpenBazaar node can have a one-to-one association with a GPG identity through the following technical mechanism: The GPG identity can provide additive trust to the existing trust of the system. To indicate that a GPG key is associated with an OpenBazaar identity and that the GPG key owner wishes to transfer the GPG trust to an OpenBazaar node, the GPG key owner cryptographically signs a binding contract which contains the OpenBazaar GUID of the target node, and potentially a time frame for which the signature is valid. The GPG-signed contract can then be signed with the OpenBazaar cryptographic key to indicate that the OpenBazaar node operator authorizes GPG trust to be used for their node. The double signed contract can then be included in the metadata associated with the OpenBazaar node and distributed through the OpenBazaar distributed hash table. Each client can inter-process communicate with the GPG software instance installed on the same platform to obtain access to existing keys and signatures.

Nevertheless, it is advised not to include such an implementation in the canonical client, as traditional GPG webs-of-trust are identity-verifying, not trust-verifying, as explored in the section above. Furthermore, the GPG web-of-trust does not offer any assurances on pseudonymity. While it is possible to exchange GPG signatures anonymously, the GPG web-of-trust is typically based on global topological knowledge of the GPG graph and is distributed through public keyservers. If a user opts-in to interconnect with the GPG web-of-trust, they are forfeiting these benefits of the OpenBazaar network.

An interconnection with the Bitcoin OTC web-of-trust is also possible. Existing trust relationships can be imported to the OpenBazaar client manually through a file, or automatically downloaded from the Bitcoin OTC IRC bot dynamically upon request, as the Bitcoin OTC website is an insecure distribution channel and does not offer HTTPS. In the dynamic downloading case, the threat model is reduced to trusting the TLS IRC PKI, which is known to be attackable by powerful third parties [DigiNotar].

This web-of-trust has the benefit of being a true-trust web-of-trust, and has a history of support by the Bitcoin community. A double signature is again required to interconnect two identities. The GPG key associated with the Bitcoin OTC network is used to cryptographically sign a binding contract similar to the one described above, and the rest of the procedure is identical to GPG identity binding.

In this case, an Achilles' heel is introduced to the software, as the user is required to trust the Bitcoin OTC web-of-trust operator and the distribution operator, both of which identities can possibly be compromised by a malicious third party. The situation can be improved if the Bitcoin OTC operator begins GPG signing the trust network, or by requiring the Bitcoin OTC trust edges to include GPG signatures by the users involved. However, the topology of the network is again public, forfeiting pseudonymity requirements. Therefore, an implementation is again not advised for the canonical OpenBazaar client at this time.

If the user is not concerned with single-points-of-failure and centralization, the web-of-trust can be temporarily bootstrapped by binding identities to existing social networking services which include edges between identities as "friendships" or "follows". For example, the Twitter and Facebook networks can be used. Such bindings can be weighted with a low score in addition to existing scores as described in the Total Trust section below [6].

Further research is required to determine how such interconnections will impact the security of the network.

In addition to the projected trust system provided by the web-of-trust, it is desired to provide some global trust in the network. This serves to allow the network to function with nodes that need to receive trust, but are not associates with other users of the network, or wish to remain pseudonymous even to their friends. In addition, this allows to bootstrap the network for someone who wishes to use it without explicitly trusting any entities.

Global trust mimics the trust given in real-world transactions towards vendors that have invested money in their business, something that can be physically verified. When a buyer visits a physical shop to purchase some item, they trust that the shop will still be there the next day in case their item is faulty; they do not expect the shop to disappear overnight. The reason for this expectation is that it would clearly be unprofitable for the vendor to open and close shops every day, as it costs money to establish a store, and the money needed to establish a store is more than the money a vendor could gain by selling a faulty product.

Similarly, hotels ask for the passport of their residents in order to be able to legally hold them accountable to limit financial risk. While it is possible to create counterfeit passports every other day, it is economically irrational to do so, as building a new identity is more costly than a couple of hotel nights.

In these situations, rational agents are economically incentivised not to cheat on transactions through physical verification of proof that it would be costly to forfeit their identity – either to create a counterfeit passport or to shut down a physical store overnight. However, in a pseudonymous digital network, such mechanisms need to be established artificially. We start by exploring some approaches to the problem that do not meet our goal: Proof-of-donation and proof-to-miner. Subsequently, we introduce two mechanisms that solve the problem, proof-of-burn and proof-of-timelock, which are combined to form the global trust score.

In all schemes, the person wishing to create trust for a pseudonymous node pays a particular amount of money, which can be provably associated with the node in question. The differentiation comes from whom the payment is addressed to.

In a proof-of-donation (also called "proof-of-charity" in the community) scheme, the pseudonym owner pays any desired amount to some organization, which is hopefully used for philanthropic or other non-profit purposes. The addresses of organizations that are allowed to receive donations would be hard-coded in the canonical OpenBazaar client and payments towards them would have been verified by direct bitcoin blockchain inspection by each client. A proof-of-donation first seems desirable, as money is transferred to organizations for good. One possible scenario could include funding the OpenBazaar project itself through this scheme.

The technical way to achieve proof-of-donation is to simply make a regular bitcoin transaction with a donation target as its output. The transaction must also include the GUID of the target OpenBazaar identity that the donation is used for.

Nevertheless, a proof-of-donation scheme is inadequate for our purposes, as it introduces an Achilles' heel. In particular, if a malicious agent is able to access the private cryptographic keys of one of the donation targets, they are able to game the system and manipulate trust arbitrarily. Compromising the private cryptographic keys can be achieved through various ways by powerful agents; for example, a secret warrant can be issued by a government ordering that the private keys are handed to the court.

This attack would work as follows: The malicious agent first generates a new OpenBazaar identity. Subsequently, they donate a small amount of bitcoin to the donation target organization they have compromised, including their OpenBazaar node as their target identity in the proof-of-donation, thereby gaining a certain amount of trust. They then use the private keys they control to give the money back to themselves, potentially through a certain number of intermediaries to avoid trackability. Finally, they repeat the process an arbitrary amount of times to gain any amount of trust desired, thereby gaming the system.