A Review of P300 in Assistive Communication Technology: a Brief Report to Inform Product Development

Assistive and augmentative communication (AAC) devices are used as treatment for individuals with speech and motor disabilities to allow for functional and meaningful communication which would otherwise be impossible ("Formal Request for National Coverage Decision for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Devices," 1999). As the ability to communicate is critical for quality of life, such devices are necessary. In addition, as the range of impairments affecting speech are diverse, end-users require different device features tailored to their needs. We aim to address this issue by harnessing the power of the P300 event-related potential as measured by the low-cost OpenBCI, an open-source brain-computer interface platform, to allow for text communication that is solely neural based (see README.md for reproducibility instructions).

Locked-in syndrome is a rare neurological disorder in which there is complete paralysis of all voluntary muscles except for the ones that control the movements of the eyes. Individuals with locked-in syndrome are conscious and awake, but have no ability to produce movements (outside of eye movement) or to speak (aphonia) (Smith, E. et al., 2005). Cognitive function is usually unaffected. Communication is sometimes possible through eye movements or blinking. Locked-in syndrome is caused by damaged to the pons, a part of the brainstem that contains nerve fibers that relay information to other areas of the brain (Smith, E. et al., 2005). Individuals with locked-in syndrome classically cannot consciously or voluntarily chew, swallow, breathe, speak, or produce any movements other than those involving the eyes or eyelids. In some cases, affected individuals can move their eyes up and down, but not side-to-side (Bauer et al., 1979). Affected individuals are bedridden and completely reliant on caregivers.

Locked-in syndrome is most often caused by damage to a specific part of the brainstem known as the pons. The pons contains important neuronal pathways between the cerebrum, spinal cord and cerebellum (Smith, E. et al., 2005). In locked-in syndrome there is an interruption of all the motor fibers running from grey matter in the brain via the spinal cord to the body’s muscles and also damage to the centers in the brainstem important for facial control and speaking (Feldman, M. H., 1971). Damage to the pons most often results from tissue loss due to lack of blood flow (infarct) or bleeding (hemorrhage) – less frequently it can be caused by trauma. An infarct can be caused by several different conditions such as a blood clot (thrombosis) or stroke (Hacke et al., 1988). Additional conditions that can cause locked-in syndrome include infection in certain portions of the brain, tumors, loss of the protective insulation (myelin) that surrounds nerve cells (myelinolysis), inflammation of the nerves (polymyositis), and certain disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Hayashi, H., & Oppenheimer, E. A., 2003).

Locked-in syndrome is a rare neurological disorder that affects males and females in equal numbers. Locked-in syndrome can affect individuals of all ages including children, but most often is seen in adults more at risk for brain stroke and bleeding (Bruno et al., 2011). Because cases of locked-in syndrome may go unrecognized or misdiagnosed, it is difficult to determine the actual number of individuals who have had the disorder in the general population. Emile Zola wrote in his novel Thérèse Raquin (Zola, 1992) about a paralyzed woman who “was buried alive in a dead body” and “had language only in her eyes.” Zola highlighted the locked-in condition before the medical community did.

Symptoms of the following disorders can be similar to those of locked-in syndrome. Comparisons may be useful for a differential diagnosis. Locked-in syndrome is also called pseudo-coma because affected individuals are conscious but make little body movement – like unconscious “eyes-closed” coma patients or unconscious “eye-open” vegetative state patients (Owen et al., 2006). Akinetic mutism is a rare neurological condition in which an affected individual does not move (akinetic) or talk (mute) despite being awake. Individuals with akinetic mutism have normal sleep/wake cycles, but (when awake) lie still and unresponsive, neither moving nor talking (Cravioto et al., 1960). Akinetic mutism is a form of minimally conscious state often due to vascular or traumatic damage in the midline frontal grey matter (Nagaratnam et al., 2004). A variety of conditions can cause symptoms or a clinical picture that is similar to locked-in syndrome. These disorders or conditions include Guillain-Barre syndrome, myasthenia gravis, poliomyelitis, polyneuritis or bilateral brainstem tumors. As said, locked-in syndrome can be mistaken for a vegetative state that may occur secondary to trauma or a variety of different conditions, especially if affected individuals have visual or hearing loss making the diagnosis more difficult. You can hear those around you, but you can't speak. You can feel a touch, but you can't touch back. You can see, but you can't move. That's the life of a completely locked-in patient, someone who has brain function but complete paralysis, which can be caused by stroke, traumatic brain injury, medication overdose or diseases of the circulatory or nervous system, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease) (Lulé et al., 2009). It was generally thought that completely locked-in patients were unable to communicate with the outside world -- but studies have showed otherwise (Söderholm, S., Meinander, M., & Alaranta, H. 2001).

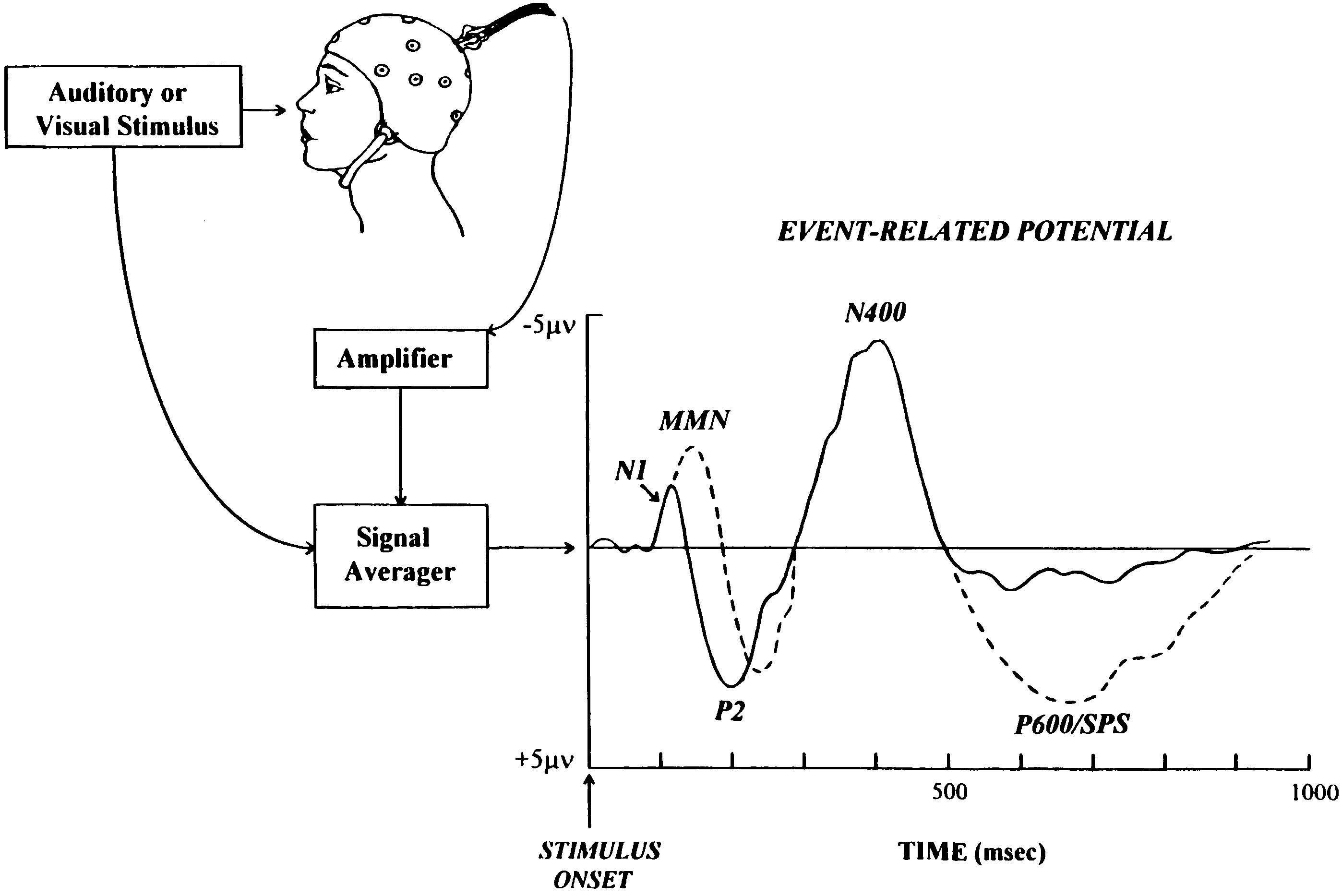

As described by Kubler, Kotchoubey, Kaiser, Wolpaw, and Birbaumer (2001), an event-related potential (ERP) is the electrical activity generated by postsynaptic potentials in the neural cortex in response to an endogenous or exogenous stimulus. In other words, an ERP is a waveform that is time locked to an event (Sur & Sinha, 2009). P300 refers to an ERP with a positive amplitude and a latency of 300-400ms following an endogenous stimulus (Kubler et al., 2001). The P300 ERP can thus be used as a neural proxy for decision-making (Twomey et al., 2015) and is widely used in BCIs as an indicator of visually rare phenomena (Machado et al., 2010).

EEG: An electroencephalogram (EEG) measures the summed electrical activity of the cerebral cortex at any given time. Measurable components of EEG signals include amplitude, frequency, cordance, power, and synchronicity. On a very broad, high-level, oscillations at different frequencies (beta waves (> 14 Hz), alpha waves (7.5 - 13 Hz), theta waves (3.5 - 7.5 Hz), and delta waves (<= 3 Hz)) are associated with specific mental states. EEG, is able to detect the strongest P300 ERP signals with Pz electrode Pz the parietal lobe (Kubler et al., 2001). The temporal resolution is extremely high, with millisecond accuracy. The trade off, however, is that EEG has very low spatial resolution compared to other neuroimaging methods, and can only measure signals from the cerebral cortex. However, EEG has a wide range of applications, both in clinical and basic science (Gui et al., 2010).

Within an experimental setting, the P300 ERP is commonly elicited using an oddball paradigm in which a participant is presented with a series of target stimuli with rare occurrences of a different stimulus. The neural response to this unexpected stimulus corresponds with a larger amplitude P300 ERP (Kubler et al., 2001).

An eample of an oddball paradigm in the visual domain: Visual stimuli are presented in a temporal sequence. The green colored circle stimulus is frequently presented and is referred to as the “frequent” or “standard” stimulus. The pink colored circle is rarely presented and is referred to as the “rare” or “deviant” or “target” stimulus. The number of standards presented between two deviants is pseudo-random. Within the context of BCI speller matrices, only the user-intended row and column will induce a P300 ERP (Machado et al., 2010).

Image source: Daltrozzo, J., & Conway, C. M. (2014)

Polacek et al. highlight three main ways for people with motor impairments to input text into an AAC device: direct selection; scanning; and pointing and gestures (Polacek, Sporka, & Slavik, 2017). Direct selection requires users to select a key out of a set of keys, which is usually organized in a way that reduces the number of keys in the set (e.g. clustering of letters). Scanning requires only one signal from the user; they can trigger a step (move onto the next option or ask the computer to scan automatically through the options) or make a selection. This signal from the user can come from a button that must be pressed, as well as from non-traditional input methods (e.g. bite switch, eye blinks, muscle contractions, nonverbal vocalizations). Finally, pointing and gestures require interaction with a mouse or joystick (if motor skills are sufficient), or the use of head movement, eye movement and biosignals such as muscle contractions (EMG) or brain signals (EEG). Existing devices take advantage of these input methods differently, depending on the severity of the user’s motor impairment.

AAC devices can also be classified by their type of speech output: they may generate either digitized or synthesized speech, with access by touch or some other modality ("Formal Request for National Coverage Decision for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Devices," 1999). Devices with digitized speech output rely on pre-recorded sentences vocalized by the user or caregiver, and limit the output to this set of pre-recordings. For instance, the GoTalk Pocket, developed by the Attainment Company, is a simple communication support that allows users to display pictures and press buttons (this requires some motor ability) in order to compose up to 30 pre-recorded messages (Attainment Company, 2018). Using an overlay software, additional images can be added to personalize the available messages. There also exist more high-tech options, such as the :prose app by Cognixion, which allows users to associate pre-registered sentences to swipe and tap gestures on their mobile device (Cognixion, 2018). For those with more severe motor impairment, a hands-free option makes use of the Emotiv EEG headset to allow control via brain waves and facial gestures. There are also numerous examples of experimental devices which have not yet succeeded in translating to commercial products. For instance, MindScribe, whose prototype has been tested in Japan for 4 years on over 2000 patients, aims to assist users with ALS and locked-in syndrome using the NeuroSky EEG system (Neurosky, 2016). This device allows users to select one of four messages: yes, no, happy (or positive response) and sad (or negative response).

On the other hand, devices with synthesized speech output use computer-generated speech, and therefore allow for a wider range of thoughts to be expressed. As previously described, devices can be interacted with using multiple modalities, which vary depending on the severity of impairment of the user. In particular, devices that do not require the user to type are of interest for those with more severe motor impairments. Talk to Me Technologies’ eyespeak speech-generation device caters to a wide range of abilities, allowing users to type, touch symbols or use eye- and head-tracking to compose messages (Talk to Me Technologies, 2018). Researchers at Microsoft are also developing a mobile application called Gazespeak, which tracks eye movements on a cell phone and leverages predictive spelling to interpret eye movements and rapidly generate speech (Zhang, Kulkarni, & Morris, 2017).

There also exist more low-tech options with no speech output, but rather rely on interpretation by another individual, such as a caregiver. The MegaBee, for example, is an electronic, hand-held writing tablet originally developed for people with locked-in syndrome. It provides caregivers with a grid that allows for more effective conversion of eye blinks to letters (E2L Limited, 2018). Other forms of nonverbal communication, such as vibration and light, are employed by products such as the Smartstones Touch. This simple, stone-shaped device relies on touch (swipes, taps, squeezes and arm gestures) in order to send vibrations, light patterns, text and voice alerts to another Smartstone or a mobile device (Smartstones Touch, 2015). This may be useful for children and individuals with reduced mobility to send a rapid signal to a loved one to let them know they’re okay.

The AAC industry has resulted in the emergence of numerous products, but few are targeted to the needs of end-users with little to no mobility. In addition, numerous prototypes fail to translate into commercial products. Some barriers to this translation are cost, speed and lack of consideration for end-users’ needs (Blain-Moraes, Schaff, Gruis, Huggins, & Wren, 2012; Gladman, Dharamshi, & Zinman, 2014), all of which we aim to address with our EEG speller.

For AAC technology to be practical and usable by target populations, consumer opinions must be taken into consideration. Indeed, abandonment and non-use of technology occur when end-users’ opinions are not accounted for during product development (Blain-Moraes et al., 2012). Studies that gathered feedback from potential brain-computer interface (BCI) end-users and their caregivers describe specific issues with current EEG-based AAC devices, which are highlighted below.

Eye strain, cognitive fatigue and anxiety were reported due to the flashing of the visual display used in most P300 spellers to scan through letter selections (Blain-Moraes et al., 2012). One study demonstrated that varying the patterns of stimulus presentation resulted in less visual fatigue (Townsend et al., 2010). Adjustment of screen brightness and blue light filtering may also be considered to allow for long-duration screen use.

Most end-users report issues with the fit of the EEG cap, as well as concerns for daily use and maintenance of the cap. Pain and discomfort can result if the cap is not properly fitted to a person's’ head (Blain-Moraes et al., 2012). Bulkiness of the system, as well as the number of wires were cumbersome to some users (Kleih et al., 2011; Zickler et al., 2011). More importantly, set-up and clean-up time were highlighted as additional burdens on both users and their caregivers. In fact, the use of electrode gel requires users to wash their hair after use, which involves more work on the caregiver’s part (Kleih et al., 2011). The use of dry electrodes with shorter set-up time, as well as discrete or wireless EEG caps would therefore be more easily adopted by end-users. The importance of aesthetics depended largely on personal preference. Some users found appearance to be generally unimportant (Geronimo, Stephens, Schiff, & Simmons, 2015), while others were concerned with how fashionable and attractive the cap is (Blain-Moraes et al., 2012).

End-users highlighted the need to improve P300 speller speed, to at least 15 letters per minute, according to one survey (Geronimo et al., 2015). Two additional studies demonstrated that users did not feel the BCI spellers they were introduced to would be useable in their daily lives due to their slowness (Kleih et al., 2011; Zickler et al., 2011). According to one focus group, ALS patient-caregiver pairs do develop their own, effective forms of nonverbal communication. In fact, “these social units found that the type of communication that BCIs could offer did not provide] any additional benefit to what they had already established” (Blain-Moraes et al., 2012, p. 521). “After 58 years of marriage, she knows what I’m going to say anyway,” communicated one ALS patient (Blain-Moraes et al., 2012, p. 521). Thus, without the ability to rapidly convey thoughts, P300 hundred spellers may not be worth the hassle for some users who have developed alternative communication strategies.

Surveys and focus groups targeted towards end-users also identified interesting features that could be incorporated in future P300 devices. The ability to interface with other electronics such as mobile devices, televisions and wheelchairs was of particular interest (Zickler et al., 2011). One important application raised in a focus group composed of 8 individuals with ALS and their caregivers was that “[caregivers wanted the ability to let individuals with ALS know that they were on their way, in emergency situations or otherwise” (Blain-Moraes et al., 2012, p. 521). This would be feasible with a BCI capable of interfacing with a cell phone.

The integration of neuroscience principles, linguistics research, and artificial intelligence methods yields a low-cost, multifunctional P300-based communication tool can empowering these disabled individuals to efficiently convey complex thoughts and to connect with the world at large. Along with its accessibility, we expect that the addition of intuitive speech prediction technology and modern interface, will improve the standard for the AACs currently on the market.

Attainment Company. (2018). GoTalk Pocket. Retrieved from https://www.attainmentcompany.com/gotalk-pocket

Blain-Moraes, S., Schaff, R., Gruis, K. L., Huggins, J. E., & Wren, P. A. (2012). Barriers to and mediators of brain–computer interface user acceptance: focus group findings. Ergonomics, 55(5), 516-525. doi:10.1080/00140139.2012.661082

Bauer, G., Gerstenbrand, F., & Rumpl, E. (1979). Varieties of the locked-in syndrome. Journal of neurology, 221(2), 77-91.

Bruno, M. A., Bernheim, J. L., Ledoux, D., Pellas, F., Demertzi, A., & Laureys, S. (2011). A survey on self-assessed well-being in a cohort of chronic locked-in syndrome patients: happy majority, miserable minority. BMJ open, 1(1), e000039.

Cognixion. (2018). :prose for Education. Retrieved from http://www.speakprose.com/

Cravioto, H., Silberman, J., & Feigin, I. (1960). A clinical and pathologic study of akinetic mutism. Neurology, 10(1), 10-10.

Daltrozzo, J., & Conway, C. M. (2014). Neurocognitive mechanisms of statistical-sequential learning: what do event-related potentials tell us?. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 8, 437.

E2L Limited. (2018). MegaBee™. Retrieved from http://www.megabee.net/

Feldman, M. H. (1971). Physiological observations in a chronic case of “locked‐in” syndrome. Neurology, 21(5), 459-459.

Formal Request for National Coverage Decision for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Devices. (1999). Retrieved from http://www.augcominc.com/whatsnew/ncs5.html

Geronimo, A., Stephens, H. E., Schiff, S. J., & Simmons, Z. (2015). Acceptance of brain-computer interfaces in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration, 16(3-4), 258-264. doi:10.3109/21678421.2014.969275

Gladman, M., Dharamshi, C., & Zinman, L. (2014). Economic burden of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a Canadian study of out-of-pocket expenses. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener, 15(5-6), 426-432. doi:10.3109/21678421.2014.932382

Gui, X. U. E., Chuansheng, C. H. E. N., Zhong-Lin, L. U., & Qi, D. O. N. G. (2010). Brain imaging techniques and their applications in decision-making research. Xin li xue bao. Acta psychologica Sinica, 42(1), 120.

Hacke, W., Zeumer, H., Ferbert, A., Brückmann, H., & Del Zoppo, G. J. (1988). Intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy improves outcome in patients with acute vertebrobasilar occlusive disease. Stroke, 19(10), 1216-1222.

Hayashi, H., & Oppenheimer, E. A. (2003). ALS patients on TPPV Totally locked-in state, neurologic findings and ethical implications. Neurology, 61(1), 135-137.

Kleih, S. C., Kaufmann, T., Zickler, C., Halder, S., Leotta, F., Cincotti, F., . . . Kuebler, A. (2011). Out of the frying pan into the fire-the P300-based BCI faces real-world challenges. In J. Schouenborg, M. Garwicz, & N. Danielsen (Eds.), Brain Machine Interfaces: Implications for Science, Clinical Practice and Society (Vol. 194, pp. 27-46).

Kubler, A., Kotchoubey, B., Kaiser, J., Wolpaw, J. R., & Birbaumer, N. (2001). Brain-Computer Communication: Unlocking the Locked In. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 358–375. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.127.3.358

Lulé, D., Zickler, C., Häcker, S., Bruno, M. A., Demertzi, A., Pellas, F., ... & Kübler, A. (2009). Life can be worth living in locked-in syndrome. Progress in brain research, 177, 339-351.

Machado, S., Araújo, F., Paes, F., Velasques, B., Cunha, M., Budde, H., … Ribeiro, P. (2010). EEG-based brain-computer interfaces: An overview of basic concepts and clinical applications in neurorehabilitation. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 21(6), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1515/REVNEURO.2010.21.6.451

Nagaratnam, N., Nagaratnam, K., Ng, K., & Diu, P. (2004). Akinetic mutism following stroke. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 11(1), 25-30.

Neurosky. (2016). An ALS Communication Device Powered by Brainwaves: Meet MindScribe. Retrieved from http://neurosky.com/2016/08/an-als-communication-device-powered-by-brainwaves-meet-mindscribe/

Owen, A. M., Coleman, M. R., Boly, M., Davis, M. H., Laureys, S., & Pickard, J. D. (2006). Detecting awareness in the vegetative state. science, 313(5792), 1402-1402.

Polacek, O., Sporka, A. J., & Slavik, P. (2017). Text input for motor-impaired people. Universal Access in the Information Society, 16(1), 51-72. doi:10.1007/s10209-015-0433-0

Smartstones Touch. (2015). Smartstones: Wearable Touch Communicator. Retrieved from https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/smartstones-wearable-touch-communicator#

Smith, E., & Delargy, M. (2005). Locked-in syndrome. Bmj, 330(7488), 406-409.

Söderholm, S., Meinander, M., & Alaranta, H. (2001). Augmentative and alternative communication methods in locked-in syndrome. Journal of rehabilitation medicine, 33(5), 235-239.

Sur, S., & Sinha, V. K. (2009). Event-related potential: An overview. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 18(1), 70–73. http://doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.57865

Talk to Me Technologies. (2018). eyespeak™ 12HD. Retrieved from https://www.talktometechnologies.com/pages/eyespeak-12 Townsend, G., LaPallo, B. K., Boulay, C. B., Krusienski, D. J., Frye, G. E., Hauser, C. K., . . . Sellers, E. W. (2010). A novel P300-based brain–computer interface stimulus presentation paradigm: Moving beyond rows and columns. Clinical Neurophysiology, 121(7), 1109-1120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2010.01.030

Twomey, D. M., Murphy, P. R., Kelly, S. P., & O’Connell, R. G. (2015). The classic P300 encodes a build-to-threshold decision variable. European Journal of Neuroscience, 42(1), 1636–1643. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.12936

Zhang, X., Kulkarni, H., & Morris, M. R. (2017). Smartphone-Based Gaze Gesture Communication for People with Motor Disabilities. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, Colorado, USA.

Zickler, C., Riccio, A., Leotta, F., Hillian-Tress, S., Halder, S., Holz, E., . . . Kübler, A. (2011). A Brain-Computer Interface as Input Channel for a Standard Assistive Technology Software. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 42(4), 236-244. doi:10.1177/155005941104200409 Zola, É. (1992). Thérèse Raquin. Oxford University Press, USA.